Florence Nightingale’s revolutionary reforms reached much further than the patients she tended. The Briton, who came to the fore during the Crimean War, made nursing a reputable calling

Named after the Italian city in which she was born in 1820, Florence Nightingale is a distinctly British figure, best known for her role caring for soldiers during the Crimean War of 1853-1856.

Florence Nightingale’s work wasn’t limited to nursing: she had a lasting impact on healthcare in Britain as a whole. She was the second woman to be granted Freedom of the City of London and the first to be elected to the Royal Statistical Society. Florence Nightingale is often considered the second most important and influential woman of the Victorian era, after Queen Victoria herself.

Born into a respectable, wealthy family, Florence was expected to marry well and settle into upper class life. But she felt that nursing was her God-given calling. Her parents initially forbade her to train as a nurse as it was thought of as a poor woman’s profession.

However, her family relented after Florence’s interest and passion showed no signs of waning. She trained in Kaiserswerth in Germany for three months in 1851 and on her return to England began working at a hospital for gentlewomen on London’s Harley Street. By this time Harley Street was already the medical heart of the capital.

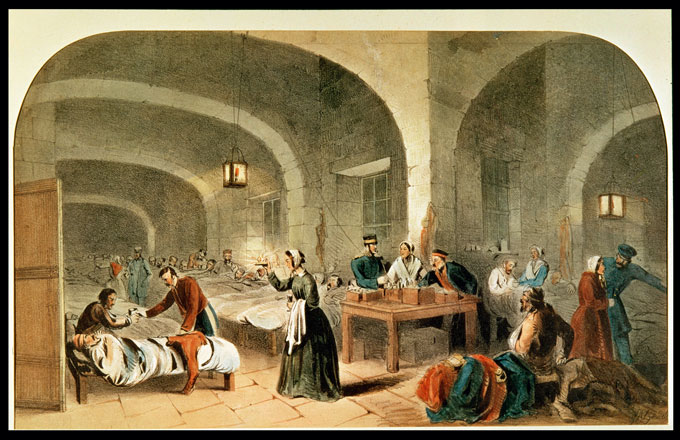

In 1853, the Crimean War broke out – a bloody conflict between Russia and an alliance of Britain, France and the Ottoman Empire (centred on modern-day Turkey). Florence was acquainted with Sidney Herbert, who was Britain’s Secretary at War at the time. Herbert asked her to manage a team of 38 nurses caring for wounded British soldiers in a hospital in Scutari.

The hospital was desperately unsanitary – rats scampered beneath the beds and disease spread quickly. Florence realised that the physical structure of the hospital could help or hinder disease, which prompted her to establish ‘Nightingale Wards’: large, open rooms with a limited number of beds to encourage circulation of fresh air and plenty of natural light. At the time this idea was revolutionary, but Florence‘s tenets are still integral to hospital wards today.

The Lady With the Lamp

Florence‘s nickname ‘The Lady with the Lamp’ actually came from a report in The Times newspaper. The editorial read: “She is a ministering angel without any exaggeration in these hospitals, and as her slender form glides quietly along each corridor, every poor fellow’s face softens with gratitude at the sight of her.”

Florence became something of a cult figure and was even immortalised in a poem, Santa Filomena, by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow: “A Lady with a lamp shall stand/In the great history of the land/A noble type of good/Heroic Womanhood.”

When she died in 1910, here obituary in The Guardian newspaper read: “In point of fact, the task before Florence Nightingale was nothing less than to save the British army.

“Without her, or at any rate without some such labour as that which she undertook, our generals would soon have been left without a single man.”

After the war, monetary gifts were bestowed on Florence Nightingale. She used these donations to set up the Nightingale Training School in 1860 at St Thomas’s Hospital in London. Once trained, nurses were sent to hospitals all over Britain, where they promoted the Nightingale model of nursing. Once again, her theories, published in Notes on Nursing (1859), established health practices that are still in existence today.

Ironically, her own life was marred by ill health. She was intermittently bedridden from 1857 onwards, and the horror of the war clearly stayed with her for all of her days. In his biography Florence Nightingale: Avenging Angel, Hugh Small argues that she broke down because she felt responsible for the deaths of 14,000 soldiers who could not be saved.

Yet her legacy endures and you can discover more about her at the Florence Nightingale Museum in London where the highlight exhibit is the Turkish lamp that she carried with her on her rounds. “It has huge symbolism,” says Natasha McEnroe, the museum’s director. “The image of this one woman changed people’s perceptions, establishing nursing as the respectable profession it is today.”

Related articlesWin a Welsh countryside getaway |

Click here to subscribe! |

© 2024

© 2024