We follow in the footsteps of the Scottish missionary, explorer and all-round Victorian hero, who fought to end the slave trade

There aren’t many ten-year-olds working in a cotton mill who would spend their first week’s wages on a Latin grammar. David Livingstone, however, toiling on the factory floor, dreamed of bigger things: becoming a medical missionary in China.

Born 19 March 1813, one of seven children living with desperately poor Calvinist parents in a single room in Blantyre, South Lanarkshire, Scotland (now the David Livingstone Centre), Livingstone continued working at the mill while studying medicine and theology.

The first of Britain’s ‘Opium Wars’ barred his way to China so, after being ordained as a missionary, he arrived in Cape Town in 1841. Horrified at the treatment of African people by the Boers and Portuguese he became a vocal advocate of the anti-slavery movement.

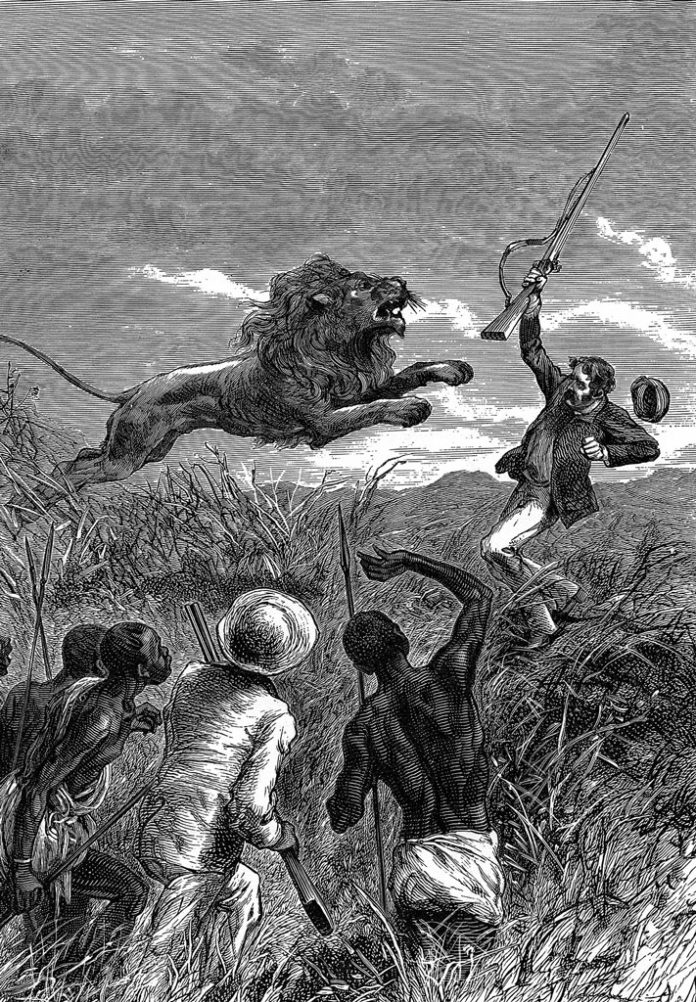

Livingstone delighted in discovery. For 15 years he was constantly on the move, exploring, spreading the gospel and familiarising himself with local people, languages and culture. He was undeterred by physical hardship and accidents, even a mauling by a lion in 1844 which left him partially disabled. He married Mary Moffat in 1845 and the couple travelled together before health and family needs forced Mary home in 1852.

Having been awarded a gold medal by the Royal Geographical Society for the first sighting of Lake Ngami, Livingstone set out again. If he could find a new route to the Atlantic coast, legitimate businesses could undercut the slave trade.

In 1855 he sighted – and named – Victoria Falls and, in 1856, he reached the mouth of the Zambezi River, becoming the first European to cross the width of southern Africa.

Now a national hero, Livingstone undertook speaking tours and wrote a bestseller. He was finally able to provide for his – still desperately poor – family. He couldn’t settle however and, in 1858, left for Africa again.

This time it was official: Livingstone was commanding an exploration of Eastern and Central Africa for the British government. Alas, he found it impossible to navigate the Zambezi by ship, and other routes proved impractical.

Personal tragedy hit. Mary died from malaria in 1862; their eldest son went to the United States where he, too, died, fighting in the Civil War.

In 1863 Livingstone returned home. He wrote another book but, restless again, secured private funding for another expedition, searching for the Nile’s source.

Forced south by Ngoni raids, some of his followers deserted him. To avoid punishment they concocted a story that Livingstone had been killed. In reality, he had become the first European to reach Lakes Ngami, Malawi and Bangweulu, then, by now a sick man, had plunged further west.

Henry Stanley, an explorer and journalist for the New York Herald, went searching for Livingstone with food and medicine. His words, on their meeting near Lake Tanganyika in October 1871, are world-famous: “Dr Livingstone, I presume.”

Livingstone continued his obsessive search for the source of the Nile. On 1 May 1873, he was found dead, kneeling by his bedside as if in prayer. David Livingstone’s body lies in Westminster Abbey. His heart is buried in Zambia, in African soil.

© 2024

© 2024