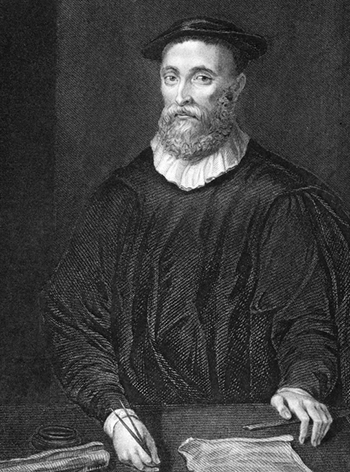

This month Melita Thomas of Tudor Times explores the life and times of Tudor John Knox, a Scottish firebrand who lived through during the reigns of King Henry VIII, Edward VI, Bloody Mary and Queen Elizabeth I

We envisage John Knox as a rabble-rousing, tub-thumping, hell-fire and brimstone preacher, calling down damnation on miserable sinners. While there is some truth in this, it’s not the whole story of one of the most influential Scotsmen ever. The real Knox was far more nuanced. He was a loving husband and father, and despite his reputation as a misogynist, had friendships with women.

The early years of Tudor John Knox

Born in the aftermath of the Battle of Flodden, Tudor John Knox attended the University of St Andrews and was ordained as a Catholic priest – not an aspect of his background that is often dwelt on.

Until he was well into his thirties, Knox was unremarkable. He lived as a notary in his native Lothian, Scotland, until he heard the preaching of the Reformer, John Rough. He ceased functioning as a priest and became tutor to the sons of local Reformist lairds. When Knox heard the inspirational George Wishart he abandoned his post. He followed Wishart, wielding a sword to protect the controversial preacher from his enemies.

The rise of Mary, Queen of Scots

The death of King James V of Scotland and the accession of Mary, Queen of Scots in 1542, reignited tensions in Scotland between the pro-English faction, led by Governor Arran, who favoured the nascent Protestant movement, and the Catholic Cardinal Beaton who favoured a French alliance.

To make an example of Wishart, Beaton had him burnt. In retaliation, a group of lairds of Fife and Lothian broke into Beaton’s castle at St Andrews and assassinated him. Knox and his pupils joined the men in the castle, where they were besieged for 18 months. It was then that Knox began his career as a preacher. Initially reluctant, he soon found that he was a master of rhetoric.

Before Knox and the others received the hoped-for succour from England, Henri II of France, a friend of the increasingly influential Queen Mother, Marie of Guise, sent ships to storm the castle. Knox was sentenced to the galleys. He endured 18 months of hard labour, only freed in 1549. His talents as a preacher and a beacon for Protestantism had reached the ears of England’s regent, the Duke of Somerset, who invited Knox to take up ministry in Berwick.

John Knox in Berwick

Knox loved his life in Berwick and, later, Newcastle. His preaching drew an ever-expanding congregation, and he became betrothed to Marjorie Bowes, daughter of an old Border family. While her father disapproved, Marjorie’s mother, Elizabeth, was one of Knox’s most passionate supporters.

Knox met John Dudley, later Duke of Northumberland, and was invited to preach in front of King Edward VI during Lent of 1552.

On the death of the Protestant king, and accession of the Catholic Queen Mary I, Knox, like many other Protestants, took refuge in Geneva, where he met Calvin and other European reformers. He was invited to lead the English congregation at Frankfurt, a role which became mired in controversy when the congregation split into factions – the Knoxians and the Coxians – over whether the English Prayer Book of 1552 should be used. Knox, although forced to accept it in England, preferred the Reformed services of the Swiss or the Huguenots.

John Knox calls for the deposition of Queen Mary I

During this period Knox wrote his famous tract – ‘The First Blast of the Trumpet against the Monstrous Regiment of Women’, mainly directed at Mary of England. Whilst Knox’s readers would generally have agreed with his views on the inferiority of women, few were prepared to support his call for deposition of female monarchs. Frankfurt lay in the lands of the Emperor Charles, cousin and ally of Queen Mary, and Knox’s intemperate language gave his rivals the opportunity to denounce him. He was advised to leave the city before the authorities arrested him.

Knox returned to Scotland and established links with the Protestant lords; especially Lord James Stewart, half-brother of Mary, Queen of Scots. While many heard his call for reform, the time was not ripe for wide-scale change, and Marie of Guise, now in control of the government, was not willing to turn a blind eye to Knox’s radical preaching. He returned to Europe, having quietly married Marjorie.

In 1559, Knox was summoned to Scotland by the Protestant Lords of the Congregation, now in open opposition to Marie. Matters came to a head when Knox’s preaching in Perth sparked off iconoclastic riots. A compromise between the Lords and Marie soon broke down and civil war erupted.

John Knox and Queen Elizabeth I

Knox secretly requested help from the new Protestant English government of Elizabeth I. He was surprised to learn that Elizabeth, although sympathetic to the Scottish lords, detested him. Nevertheless, she aided the Scottish Protestants, which, combined with the death of Marie, allowed them to triumph. The Scots Parliament of 1560 implemented Protestantism. Knox was appointed to minister in St Giles’ Kirk, in Edinburgh and took an active part in the General Assembly of the Kirk.

In 1561 this halcyon period came to an end, in Knox’s eyes, with the return of Mary, Queen of Scots, from France, to take up personal rule. Knox was convinced, before he had set eyes on her, that she would attempt to undo the Reformation and reimpose Catholicism by force.

Initially, Mary won widespread support from Catholics and Protestants. She attempted to appease Knox, inviting him to tell her of any faults he found in her. Knox responded ungraciously: it wasn’t his job to give advice to sinners – she could attend his sermons like anyone else. He criticised her court, complaining of the queen’s fondness for dancing and other light-hearted pastimes.

Politically, matters degenerated with Mary’s marriage to Lord Darnley, of which Knox strongly disapproved. One of Darnley’s most outrageous acts was the orchestration of the assassination of the queen’s secretary. This was a plot of which Knox, like everyone except Mary and the victim, was aware.

Knox denounces Mary, Queen of Scots

Darnley was assassinated in February 1567. Knox was convinced that Mary was behind the murder. His opinion was exacerbated by her marriage to the likely ring-leader, the Earl of Bothwell. Knox’s implacable opposition to Mary played a part in her deposition. Even after her imprisonment in England, Knox feared that she would return to Scotland, and continued to harangue against her.

Knox’s friend, Lord James Stewart, now Earl of Moray, became regent, and Knox hoped that Scotland would become a ‘godly’ state, like Calvinist Geneva. He was disappointed to find the Protestant lords no less self-seeking than the Catholic Church.

Scotland continued in a state of unrest as first Moray, then the Regent Lennox, were assassinated. Shortly after preaching the funeral service for Moray in autumn 1570, Knox suffered a stroke.

He spent a short period in St Andrew’s, avoiding the conflicts in Edinburgh, and had a profound influence on the Scottish ministers studying there. However, Knox soon returned to the capital, finally retiring from the ministry just before his death in November 1572.

© 2024

© 2024