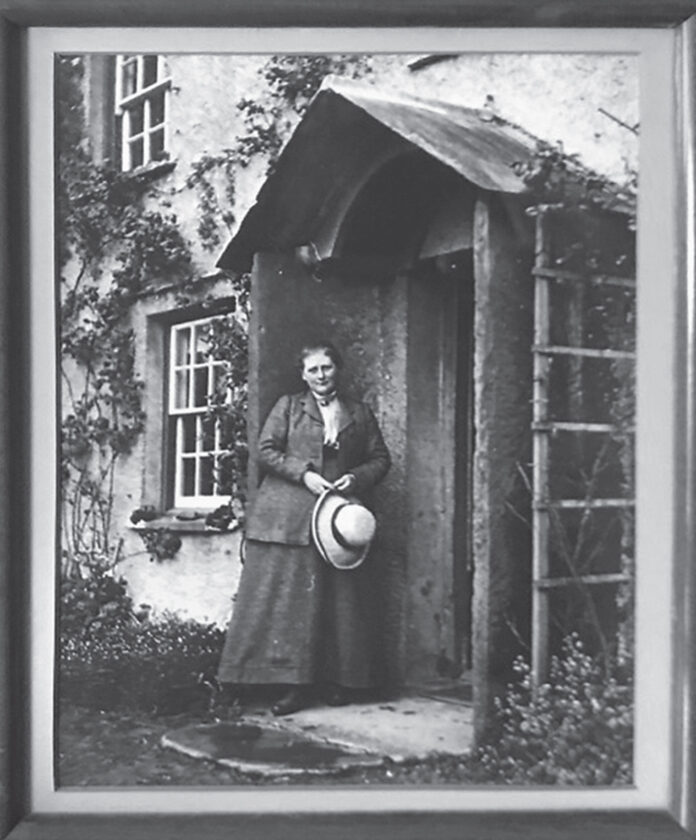

Her books are loved the world over, but the author’s unconventional life choices and passion for the Lake District make her own story a fascinating tale in itself

Words by Nadia Cohen

Say the name of Britain’s best loved children’s author in almost any corner of the world and it immediately conjures up enchanting images of mischievous animals scampering through the pages of those instantly recognisable little white books.

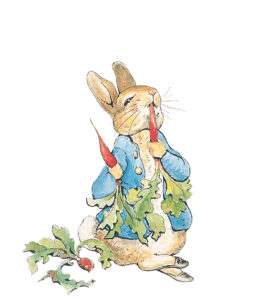

Beatrix Potter’s classic tales of Peter Rabbit, Jemima Puddle-Duck and Mrs Tiggy-Winkle have been firmly established nursery favourites for generations.

But what is less well known about the whimsical children’s author is that she was also a shrewd businesswoman, a canny marketing expert and a hardworking, often irritable, farmer who strategically bought up great swathes of land. She bequeathed thousands of acres of Britain’s picturesque Lake District to the nation, to protect it forever from the onslaught of modern development.

Beatrix was a passionate environmental campaigner, an eco-warrior and a trailblazing feminist many years before such terms had even been coined.

Born with a fiercely rebellious streak, Beatrix endured a stifling childhood, frustrated by the rigid confines of her privileged upbringing in Victorian London. From an early age her mother drummed into Beatrix that her sole purpose in life was marriage and motherhood. But it soon became abundantly clear that Beatrix was never going to be interested in either.

At a time when it was rarely considered worthwhile to send girls to school, Beatrix longed to learn something more fulfilling than piano and embroidery. And left with no choice but to educate herself, that is precisely what she did.

Left alone in the nursery, Beatrix consoled herself with studying the anatomy of animals, plants and fungi, and taught herself to draw with remarkable accuracy. She would pass her time dissecting frogs, mice and hedgehogs, which she kept hidden in her bedroom.

By the time she reached her teens Beatrix was entirely self-taught in a wide range of subjects, and confided in her intricately coded diaries: “I must draw, however poor the result. I will do something sooner or later.”

She defied the genteel social conventions of the day, refusing to settle down and churn out children. She had no interest in being paraded around high-society balls, where she was expected to secure herself whichever wealthy and well-connected man her parents Rupert

and Helen deemed a suitable match.

To pass the empty hours until she could escape her parents’ Kensington townhouse, Beatrix would send lavishly illustrated letters to her friend’s children, and wondered if her homespun stories might earn her an independent income. But her first attempt at a children’s story, The Tale of Peter Rabbit, was rejected numerous times by various publishers who all failed to spot its enormous potential. When it did eventually appear

in print – after she paid to publish it herself – Beatrix was astonished to find herself in great demand.

Soon she had an eager publisher, Norman Warne, who was not only clamouring for more stories, but wanted to marry her too. Suddenly, life was not so dull after all, and they planned to start a new life together in the Lake District.

The Potters had spent many family holidays in Cumbria, and Beatrix used her first royalty cheques to buy a bolthole for her and Norman to share after they were married.

Tragically her happiness proved short-lived. Beatrix’s fiancé died barely a month after he proposed and she fled to the Lake District to grieve in private. Retreating to their cottage, Hill Top, to nurse her broken heart was a decision that would change not only her own life but also the shape of the English landscape forever. “There’s nothing like open air for soothing present anxiety and memories of past sadness,” she wrote.

A steady stream of phenomenally popular children’s books followed Peter Rabbit, but publishing no longer brought Beatrix satisfaction once she discovered a new way of life in the rugged Cumbrian hills and fells.

She only ever felt motivated to write when she needed money to buy more farms and cottages in order to thwart ruthless developers who were eager to capitalise on the newfound popularity of the Lake District.

Within easy reach of the major industrial towns of the north, the area was becoming besieged by factory workers who were enjoying paid holidays for the first time, as a result of the new Bank Holiday Act, but Beatrix feared hotels, pubs and amusements would destroy the area’s natural beauty.

She campaigned vociferously against the march of modernisation and deliberately snapped up chunks of land next to roads to ensure they could not be widened to allow more traffic to rumble through the peaceful villages.

As soon as farms came on the market she pounced, ensuring that traditional methods were preserved too. Her portfolio of properties quickly grew to over four thousand acres, and together with her friend Canon Hardwicke Rawnsley, Beatrix planted the first seeds of the National Trust.

Beatrix shared Rawnsley’s fear that the influx of visitors would inevitably start to erode, and ultimately destroy, the region. Rawnsley confided to Beatrix that he had a masterplan to save the Lake District, and she joined his passionate crusade to create a nationwide charity. His aim was to secure funds to purchase areas of outstanding natural beauty under threat of ruin, as well as protecting stately homes and other places of historical interest which faced demolition.

Beatrix and Rawnsley dreamt that one day their charity would preserve these endangered places in perpetuity on behalf of the entire British nation. Their vision meant that beauty spots and stately homes would become accessible to everybody, not just the wealthy aristocracy and their private visitors.

Beatrix was impressed by Rawnsley’s sense of altruism and the way he travelled tirelessly, storming planning meetings, terrifying council committees and tackling anybody who dared to propose plans for an ugly or unsympathetic development.

Of course it was highly unusual for a single woman to buy property at that time without the help of a husband or father, but Beatrix found an ally in a local solicitor named William Heelis, who cheerfully helped smooth the sales through. Slowly they fell in love and she finally married at the age of 47 – far too late to start a family – and became known locally as Mrs Heelis, his rather stout wife.

The couple lived frugally in two neighbouring cottages, and Beatrix described herself and William as being “like two horses in front of the same plough, walking so steadily beside each other.”

Beatrix also cared deeply about the welfare of women. When she realised that mothers in remote locations were dying in childbirth she paid for a District Nurse, and always insisted on paying her workers’ wages directly to their wives. She feared that men were liable to spend the cash “inappropriately”.

Tant Benson, a shepherd at one of her vast estates, Troutbeck Park, recalled: “I was there 17 years and she never paid me once. She always gave the money to the missus. ‘That’s where it should be,’ she would say, ‘for the housekeeping’. She never paid me – not once.”

Although Beatrix’s books and accompanying merchandise led to global fame and a vast fortune, she always kept her status concealed in the close-knit rural community where she retreated for the rest of her life. She refused to travel abroad to promote her books, and never gave interviews.

By today’s standards Beatrix would have been a millionaire many times over, but she cared so little for the trappings of wealth that she was often mistaken for a vagrant as she stomped through the lanes. She did not even have electricity installed in her house, although she insisted it ran through all her barns to boost productivity.

Beatrix relished being reclusive, indeed most of her neighbours only discovered her true identity after reading her obituaries, but her extraordinary legacy lingers to this day.

Not only did Beatrix alter the landscape of children’s literature, but she also left a remarkable gift to the British people when she bequeathed thousands of acres of farmland to the National Trust, to be protected and cherished in her memory forever.

Nadia Cohen’s book, The Real Beatrix Potter, is out now (£14.99, www.pen-and-sword.co.uk).

© 2024

© 2024