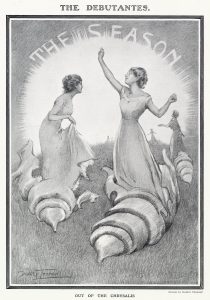

With a new series of Bridgerton – and its world of fancy frocks and high-society balls – soon to hit our screens, we take a dance through the history of debutantes

Words by Felicity Day

It was such a peculiar thing to have done,” recalled one of Britain’s last official debutantes, the 1,400 young women who swept a reverential curtsey to our late Queen and Prince Philip at Buckingham Palace in the spring of 1958, decked out in Dior-esque day dresses, demure hats and dainty gloves.

Peculiar seemed the word for it by then, on the cusp of the Swinging Sixties, in a year which saw Britain’s first rock and roll single hit the charts, the launch of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and the appointment of the first female bank manager. But as they clipped in their court shoes out of the palace gates, ready to embark on a heady round of Mayfair cocktail parties and countryhouse balls, 1958’s debutantes were treading a wellworn path.

They followed in the footsteps of generations of women born into the upper echelons of British society, who had passed through just the same rite of passage; those whose families migrated from their country seat to a house in the capital each year in early spring, to participate in the several-month-long social whirl that was the London ‘Season’.

Synonymous with husband-hunting debutantes long before shows like Bridgerton and Downton Abbey hit our screens, the Season actually owed its existence to Parliament. Its lavish parties were entertainment for the elite families who began flocking to ‘town’ in the winter for its annual sessions in the early 18th century, only to return to the country around July, when the summer stench made London intolerable.

It was soon recognised as a perfect arena for matchmaking, but seems only to have acquired its formal link with young ladies making the leap from schoolroom to society during the reign of King George III and Queen Charlotte, when aristocratic daughters began to be routinely introduced to the Queen. Not at an annual ball, as is often said, but at one of her ‘Drawing- Rooms’ – afternoon receptions held regularly at St James’s Palace or Buckingham House. Charlotte would proffer either a cheek or hand for these first debutantes to kiss (depending on their father’s rank), graciously acknowledge their curtsey, and offer a few kind words, the whole ritual sending them off to make a match with her seal of approval.

For the Georgian debutante, court presentation was more of an ordeal than it generally looks on TV. Until 1820, protocol demanded that they don the wide, hooped gowns that had fallen out of fashion after the 1750s – heavy and hot to wear, ludicrously difficult to manoeuvre through doorways or sit down in, and cumbersome for curtseying. What followed was better fun for girls of seventeen or eighteen: extravagant ‘coming-out’ balls, where the guests could number a thousand and the dancing could go on until 5am; and admission to the notoriously exclusive assemblies at Almack’s club.

Still, the ritual of court presentation was firmly rooted in aristocratic life by Victoria’s reign. In fact, it had become almost a necessary passport for socialising in high-society circles; by the 1850s, debutantes could even acquire a certificate as proof they had made a pilgrimage to the palace. Guide books told prospective candidates if they were eligible – daughters of cabinet members, barristers and military officers were in, daughters of solicitors and tradesmen were not – and talked them through the now-complicated procedures, which included petitioning in advance with the name of their sponsor, who had to have been presented at court herself. While the hoops were gone, the dress code remained strict: gowns with trains were a necessity, as were feathered head-dresses and lace lappets or veils.

Shrouded in new etiquette – including the introduction of dance cards or ‘programmes’ so debutantes (and their parents) could keep track of their partners at balls – the Season had become a serious business. Society having turned against overtly arranged marriages, sending offspring out into ballrooms packed with only suitable partners to make a choice for themselves was the next best thing. And since a splendid match had the power to make the whole family richer and their social position more secure, many real-life mamas approached what one Earl’s daughter dryly called ‘spring campaigning’ with determination. A debutante could expect to waltz her way through several parties in a single evening, several nights in a row, each and every week. Most were content to co-operate; without the opportunities or education to provide for themselves financially, marriage was their best chance to break free of their childhood home.

‘Debbery’ (as it became affectionately known) was revitalised in the 1920s and 30s. Party-loving King Edward VII had already shaken up the old court ritual, introducing evening presentations which lasted into the early hours, and it was these that returned with a bang after a suspension during the First World War. Newly glamorous debutantes, with shingled hair and lipstick, queued on the Mall in chauffeur-driven Daimlers or Rolls-Royces, tailed by press photographers as they crawled towards the palace, who trained their lens through the windows, catching them snacking on pâté sandwiches and champagne.

There were the same ‘coming out’ parties night after night, though the inter-war ‘deb’ might fill her dance card hours in advance over the telephone, and the daring ones didn’t bother, preferring to sneak off to a nightclub with a dashing man (a ‘debs’ delight’). The Season was less consciously a marriage market, but mamas were as involved as ever: at lunches, debs recalled, they would swap details of the men who should make it onto guest lists, eliminating those NSIT (Not Safe in Taxis) or MSC (Makes Skin Creep).

The money still flowed, too. Mayfair dressmakers specialised in designing court gowns, conventionally white by 1900. Schools like Madame Vacani’s – which “held a kind of royal warrant for the curtsey” according to one former pupil – taught scores of debs to dance, and handle their train. And some well-born, but no longer well-off women earned sizeable sums from presenting girls whose mothers were unqualified as a sponsor.

debutantes to curtsey in 1929. Credit: Chroma Collection / Alamy

It was the Second World War that marked the beginning of the end. After another wartime suspension, afternoon court presentations were brought back in 1947, but the old splendour and excitement were harder to revive in a bomb-damaged London, subject to rationing. Would-be debs had begun working, or studying, and aristocratic daddies were feeling the pinch, thanks to the post-war tax regime. Age-old concerns about exclusivity were echoing more loudly, too. “We had to stop it,” Princess Margaret reputedly said, “every tart in London was getting in.”

Queen Elizabeth did call a permanent halt to presentations at the palace in 1958, but the Season limped on, with Queen Charlotte’s ball – a charity event established in 1925, at which debs curtsied to a giant white cake – for its focal point.

This is an extract, read the full feature in the January/February 2024 issue of BRITAIN, available to buy here from Friday 8 December.

Read more:

BRITAIN Magazine’s 12 Days of Christmas Advent Calendar Prize Giveaway

© 2024

© 2024