Founded by kind-hearted Victorians, and the inspiration for one of Roald Dahl’s most famous books, how did Cadbury’s become Britain’s best-loved chocolate brand? We explore the history of Cadbury’s chocolate here…

Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory is the stuff of children’s fantasies, with its edible flowers and eatable pillows, its sugarpowered elevator and enticing chocolate river.

No real-world chocolate works could ever match the magic of the one that bursts out of the pages of Roald Dahl’s beloved book about Charlie Bucket and the eccentric chocolatier, starring in his own spin-off film this Christmas. But if any can lay claim to be the inspiration for Dahl’s extraordinary creation, it has to be Cadbury’s.

It was Britain’s most famous chocolate firm that once gave Dahl the chance to experience something of the thrill that his schoolboy Charlie feels on seeing the incredible experiments going on behind closed doors in Wonka’s Oompa-Loompa-powered empire. As pupils at Repton school in Derbyshire in the 1930s, Roald and his schoolmates were recruited as Cadbury taste-testers, receiving parcels of chocolate creations direct from their inventing room to rate. A ‘clever stunt’ an adult Dahl called it, but acknowledged that those parcels had sparked plentiful daydreams about working in such a hallowed space and, without doubt, given him the idea for his much-loved book.

Cadbury’s own, equally compelling, story first began in the 1820s, when Quaker John Cadbury started out in the chocolate business in Birmingham, initially as a retailer, then a manufacturer.

Like all of his competitors, it was drinking chocolate he sold, no-one yet having found a way to turn raw cocoa beans into the edible chocolate that will fly off the shelves this Christmastime.

However, in its drinking form – and as a flavouring for desserts – chocolate had plenty of fans. First brought to England in the mid-1600s, innovations in the late Georgian era had provided a means of mass production, and high import duties on the beans had been slashed, so that what had been the sole preserve of the elite – only sipped daintily from small dishes in aristocratic drawing rooms, and slurped by gossiping, gambling men of means in London’s chocolate houses – was something even the modestly prosperous could afford to put in their shopping baskets.

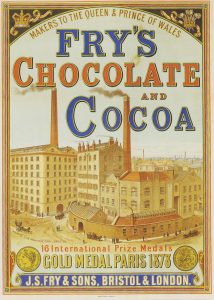

Chief among the nation’s chocolatiers was J.S. Fry & Sons, who had the largest cocoa works in the world in Bristol and a sales network stretching across 50 British towns. But competition also came from the Taylors in London and the Rowntrees in York, where the Terry family were also making a stir with chocolate-flavoured confectionery.

Both the Frys and the Rowntrees were Quakers too, similarly attracted to the trade by cocoa’s potential to keep poor souls from the temptations of the gin shop. Hard as it is to believe of a brand that’s recognised all the world over today, while names like Fry’s are almost forgotten, Cadbury once trailed behind.

Especially after 1847, when Fry’s hit upon a recipe for a chocolate paste that could be poured into a mould and set, creating Britain’s first chocolate bar for eating. In fact, by 1861, when two of John Cadbury’s sons stepped in to see if the family business could be saved, it was on the brink of bankruptcy. The only reason we know the Cadbury name is because of the determination of 25-year-old Richard and his brother George, four years his junior, who were sorely tempted to begin again with a new business, rather than “pull up a decayed one which had a bad name”.

But they did not, and instead pulled off an impressive turnaround, thanks to a cash injection (of their entire maternal inheritance), a canny trip to Holland and a clever piece of marketing. Aware that most British manufacturers bulked out their cocoa with fillers of some kind – from potato flour at best, to iron filings at worst – the brothers persuaded a Dutch rival to sell them a patented cocoa press that allowed them to produce Britain’s first entirely unadulterated variety, which they advertised as ‘Absolutely Pure, Therefore Best’.

Though not a particularly catchy slogan by modern standards, its message resonated with the health-conscious Victorians and, suddenly, Cadbury’s accounts started to look a whole lot sweeter – helped by the self-denial of its two young leaders, who had given up buying even small luxuries like tea and newspapers, not to mention become their own travelling salesmen and stock pickers.

They scored a second hit in 1868 with their ‘Fancy Box’ – the first mass-market box of filled chocolates, all bearing alluringly exotic French names. But it was Fry’s ‘Chocolate Cream’ bar that was the big seller in eating chocolate, and Fry’s who gave Britain its first Easter egg in 1873, 150 years ago this year.

Competition was fierce, and as all the manufacturers tried to nibble away at their competitors’ market share, tales abounded of spies infiltrating rival factories, and former employees being persuaded to share trade secrets for a tasty fee – stories said to have inspired the backstory Dahl gave to Willy Wonka, forced to close his own works because of industrial espionage.

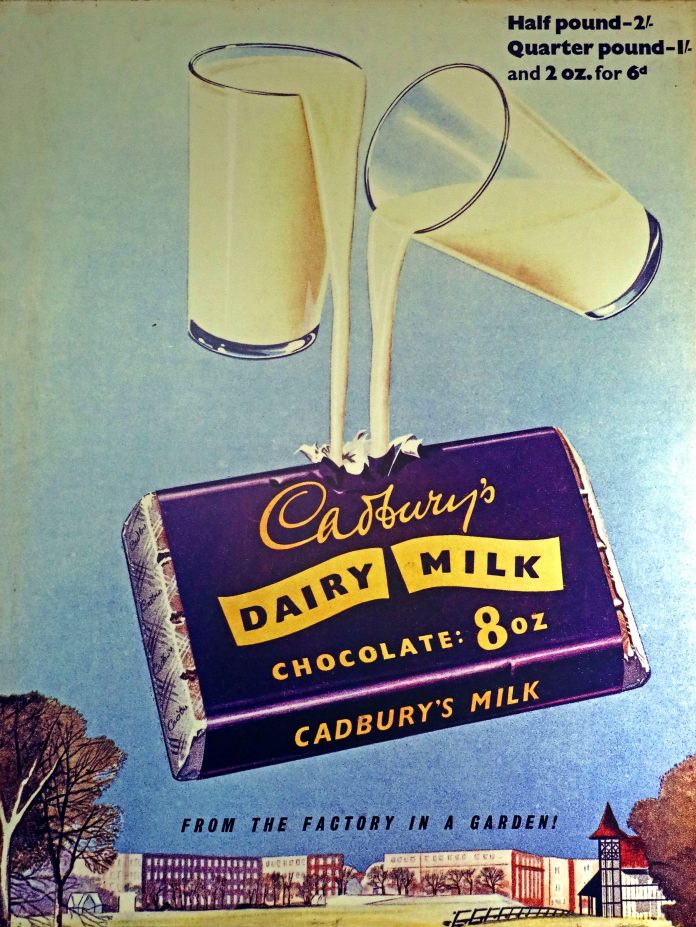

Cadbury, however, thrived, finding a breakthrough recipe for milk chocolate that became a British favourite (called ‘Dairy Maid’ until a schoolgirl suggested that ‘Dairy Milk’ sounded daintier). By 1910, the firm that had so nearly folded was outselling its rivals. By the end of the First World War, it had gobbled up Fry’s in a merger.

But success was never about profits for the Quaker pair at the helm. It might simply have been good business sense to add an extra penny a day to the wages of every worker who maintained sufficient willpower not to tuck into their product, but they were also among the first British employers to introduce half-days off, and to offer sick pay and pensions. And the real golden ticket for their employees was Bournville.

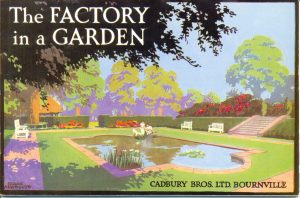

The first British village that chocolate built (it would be followed by Joseph Rowntree’s New Earswick, near York), it was a 14-acre meadow just outside Birmingham when the Cadburys bought it in 1878, deciding to move their production away from the city slums, and surround their staff with “pleasant and wholesome sights, sounds and conditions” – a decision mocked by other businessmen, who foretold financial disaster.

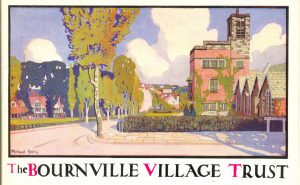

But the brothers pressed on with “a factory in a garden” for their workforce, and by 1900, it had expanded enormously, offering everything from cottages with vegetable gardens, to schools, a swimming pool and cricket pitch – though true to their Quaker principles, no pub!

Bournville survives today as a leafy suburb of the city the brothers sought to escape – and provides one final, fascinating parallel between fact and fiction. For just as Roald Dahl’s story ends with Willy Wonka gifting the chocolate factory that has been his life’s work to Charlie Bucket, so, too, did George Cadbury give away a huge chunk of his chocolate fortune, turning the Bournville model village he had funded into a charitable trust to benefit the working classes. The Cadburys didn’t just know how to make good chocolate; they knew how to make it a force for good, too.

This is an extract, read the full feature in the November/December 2023 issue of BRITAIN, available to buy here from Friday 6 October.

Read more:

© 2024

© 2024