While 1066 is the date scored into Anglophiles’ minds as the last major invasion of Britain, a lesser-known offensive centuries later has all but escaped the history books

Words and images: Simon Whaley

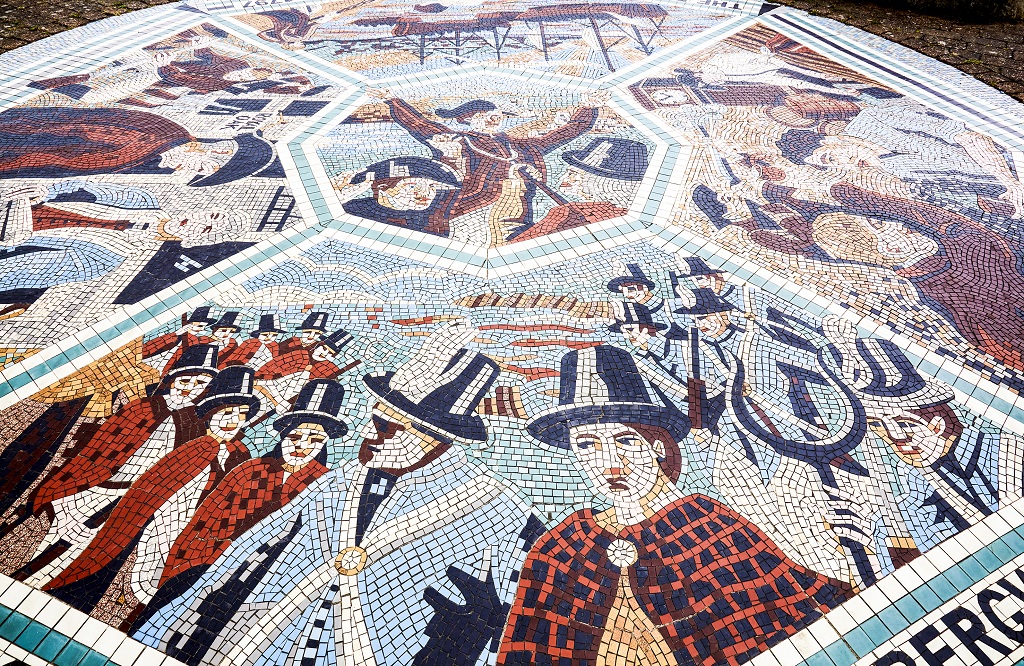

In the early hours of 23 February 1797, 1,400 French troops invaded Britain. They were the

first hostile foreign troops to set foot on British soil since the Norman invasion of 1066.

They scaled the 160-foot rugged Pembrokeshire cliffs at Carregwastad Point, three miles west of Fishguard, in West Wales. This beautiful but isolated headland juts into the Irish Sea and is so windswept the trees have a permanent stoop.

Led by Colonel William Tate, an Irish-American who fought against the British during the American War of Independence, their mission was to create an uprising among Britain’s rural peasantry. They hoped this would overthrow the British Government, and further the cause of the French Revolution, which was raging across the Channel.

However, these were not France’s finest men. Napoleon had the best soldiers fighting elsewhere, so Tate’s force, who called themselves La Légion Noir (the Black Legion), comprised 600 French soldiers and 800 newly released prisoners, some of whom still wore wrist and ankle shackles. The original plan was to sail into the Bristol Channel, land and capture Bristol – then Britain’s second-largest city – before moving northwards toward Chester and Liverpool.

But an ill wind blew the invading force’s four ships off-course, forcing them around St David’s Head into the relative shelter of Cardigan Bay. Under the cover of darkness, 16 boats shuttled back and forth, ferrying ashore their ammunition, finally completing the task by 4am. Next, they had to transport it up the precipitous cliffs; eight men lost their lives in the process.

Immediately, the French troops headed inland, and in less than a mile, seized the first property they found, Tre-Howel, which Tate made his command centre. While they were well stocked with ammunition, they’d brought little else in the way of provisions, and many of the troops hadn’t had a decent meal since leaving France. At daybreak, Tate ordered small groups of his men to reconnoitre the area, find some provisions and secure some horses.

In reality, his troops ransacked and looted isolated farmsteads and smallholdings, capturing chickens, pigs and sheep, frightening petrified locals who fled and raised the alarm.

The troops also discovered large quantities of wine in many of the remote farms, which locals had salvaged from a Portuguese shipwreck a few months previously. At the medieval Llanwnda Church, French soldiers smashed pews to create firewood and ripped pages from a Bible and the parish records to light them.

© 2024

© 2024