The North Wales Borderlands that nestle between Chester and Snowdonia have lush landscapes, famous fortresses and historic houses

|

|

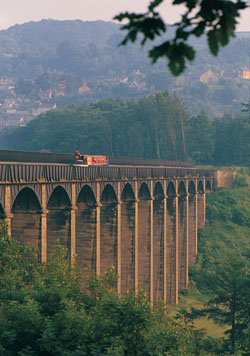

Walking along the towpath admiring a gaily-painted bright narrowboat gliding ahead along the canal, I stopped short and caught my breath. The horse-drawn boat moved serenely ahead but beyond the handrail the land fell away below me until suddenly I was walking high above the branches of mature oak trees.

This is the Pontcysyllte Aqueduct near Llangollen, one of the marvels that draws visitors to the North Wales Borderlands. The great Georgian engineer Thomas Telford faced huge challenges in building a canal over steep hills and deep valleys, but constructing this stream in the sky – its sections sealed with Welsh flannel, sugar syrup and lead – meant no need for long flights of locks.

The North Wales Borderlands are always magnificent from above, as I’d known for years – I was born in the Borderlands, lived here as a child, and still visit frequently to gaze down on the verdant valleys from the heather-clad slopes of the Clwydian Hills. But while the summits are always magnificent, the valleys are wonderful too, I remembered, as I meandered over a stone bridge to admire the aqueduct from below.

Nestling between the elegant city of Chester and the peaks of Snowdonia, the North Wales Borderlands were the scene for years of conflict between the English and the Welsh – the powerful King Offa’s 8th-century border is now the dramatic Offa’s Dyke trail which runs over the Clwydian Hills towards the coast. Close to the town of Mold, the hills are gentle enough to explore even on chilly days.

And those gracious hills are rich in signs of their earliest inhabitants. On a crisp clear day, I turned my back on the meandering Offa’s Dyke path to the top of Moel Famau, the highest summit in the range and where the Jubilee tower, built by local people in George III’s reign, was soon reduced to a single storey by winter storms, and clambered up the steeper slopes of Foel Fenlli. Standing beside the banks which mark the entrance to the ancient hill fort, you can almost feel the spirit of the people who defended themselves here and in the nearby Iron Age hill forts of Moel Arthur, Moel y Gaer and Penycloddiau.

Many a visitor to the Borderlands gazes down from a hill and falls in love with a valley. So, in 1780, the ‘Ladies of Llangollen’ (Lady Eleanor Butler and The Honourable Sarah Ponsonby) escaped the constraints of their aristocratic Irish background to gaze down on the town from the ruinous castle of Dinas Brân, calling it “the beautifullest country in the world”. They set up home together in the idyllic black-and-white house Plas Newydd in Llangollen, drawing Romantics such as Wordsworth and Sir Walter Scott to their home.

Other eminent figures came too – the painter Turner was inspired by the soaring ruinous arches of the Cistercian abbey which is Valle Crucis, and visitors today forgive him for using just a little artistic licence in his paintings such as The ruins of Valle Crucis Abbey with Dinas Brân beyond, 1794-5 where he relocated Dinas Brân to within sight of the ruins.

Today the valley is filled with plumes of steam from the railway lovingly restored by enthusiastic volunteers who run the station and drive the magnificent steam engines too. Other willing volunteers throw their energies into organising the International Music Eisteddfod, which fills the valley with song each July.

|

| 14th-century Chirk Castle, built for Edward I |

Just a few miles away, the huge bulk of Chirk Castle guards the entrance to the Ceiriog Valley, which the statesman David Lloyd George called “a little bit of heaven on earth”. A long slow stroll through the valley gives tantalising glimpses of Chirk’s own aqueduct, with the shimmeringRiver Dee far below, and idyllic villages lost in time.

“Former ages always seem very close in this part of their world,” said John Davies, my host at bed and breakfast Ty Derw, when I checked in to my room with its exposed beams in the beautiful Vale of Clwyd. This was the verdant valley I had gazed down on so many times from the summits of the hills, and rich in history it is too. “Some of the beams in your room are from old sailing ships,” John mused. “The history of this area is linked to Liverpool, just across Liverpool Bay. Many of the ships’ captains lived around here, and ships would be broken up at Rhuddlan and the timber used for houses.”

Just a few miles away in the historic market town of Ruthin, with its winding streets dominated by the rebuilt Ruthin Castle, former centuries seem incredibly close. The 15th-century hall-house Nantclwyd y Dre has now been restored so you can travel back in time, from the 1940s to the schoolroom for young ladies who studied here, back through Jacobean and Georgian times in the evocative bedchambers, to the grand 17th-century study, and to the medieval chamber where the lead badges from shrines still adorn the hat of the pilgrim who journeyed to Rome – a document detailing his pilgrimage was found hidden in the house.

And nowhere does the past seem as painfully close as in Ruthin Gaol, where you can almost taste the thin oatmeal gruel that made up prisoners’ breakfast and dinner, with only a small serving of bread and potatoes for lunch. Women convicted of pilfering to feed and clothe their families faced deportation to Botany Bay, or spells of hard labour in jail with their children beside them if there was no one else to care for them. And yet this jail was built in 1775, as the inscription over the door reads, because the magistrates were “sensible of the miserable state of the ancient prison, [and] in compassion to the unfortunate.”

Then on to Denbigh, where the castle gives sweeping views over the Clwydian Hills and towards Snowdonia. Pausing at the threshold, I shuddered at the murder holes which made intruders horribly vulnerable to attack from above, and peered into the dank green dungeon. Built by local lord Henry de Lacy as a key part of Edward I’s ring of castles (which also included Caernarfon), the walls are so massive that it is almost impossible to believe that the partly-built castle was taken by the Welsh, and strengthened even further once it was recaptured.

Those massive castles dominate this area, I mused as I gazed out across the Dee Estuary from Flint Castle, dating back to the 13th century, where children still roll down the grassy banks of the moat just as I once did. Gulls swoop over the ruins and sea birds strut the sandbanks as I explored the worn and winding stairs that were once trodden by royalty.

|

| The ruins of Dinas Bran, near Llangollen |

Even before the might of the English kings, though, came the compelling power of Christianity. After being exiled from Scotland in the sixth century, St Kentigern threw his energies into the newly-established monastery at Llanelwy, leaving it in the hands of his protégé St Asaph on his return to Scotland. Gazing up at the soaring heights of Britain’s smallest cathedral in St Asaph – the former Llanelwy – I could almost feel the presence of the two saints commemorated in stained glass windows there, and the fury of the rebels led by Owain Glyndwr who ransacked the place in 1402.

Violence, which racked the Borderlands over the centuries, has now given way to tranquillity, and so too in the town of Holywell. Dubbed the Lourdes of Wales for the healing powers of St Winefride’s Well, the bubbling well has drawn pilgrims for 1,300 years: King Henry V walked here to give thanks for his Agincourt victory. The 7th-century aristocrat Winefride was attacked by Caradog, goes the story, who cut off her head with his sword. Legend has it that she was restored to life by the holy man Beuno, and the well sprang from this very spot.

Now housed in a glorious 16th-century Gothic building, the well still draws the faithful for a cure – and nearby lie abandoned crutches, and the testaments of those who have bathed in the waters for a cure. Nestling close to those glorious hills, Holywell and the other unique treasures around it mean there is always plenty to see and do in the North Wales Borderlands. I’ll be back, and soon.

How to get there

By road: the North Wales Borderlands area is within easy reach of the national motorway network, and is well served by main roads including the A55 Expressway and the A5 London to Holyhead route.

By rail: there are direct links from London, Holyhead, Chester and Manchester with Virgin Trains (Tel: 0845 722 2333; www.virgintrains.co.uk). For timetables, contact National Rail 0845 748 4950; www.nationalrail.co.uk.

By air: both Manchester International Airport (www.manchesterairport.co.uk) and Liverpool John Lennon Airport (www.liverpooljohnlennonairport.com) are easily accessible and less than an hour’s drive from the North Wales Borderlands.

Don’t miss

The Horseshoe Pass The dramatic road north from Llangollen which winds over the hilltops with spectacular views.

Erddig (National Trust), Wrexham This unique stately home was also a well-loved family home with eloquent testimonies to loyal servants. Tel: (01978) 355314 or visit www.nationaltrust.org.uk.

The parish church of St Giles, Wrexham Explore this church dedicated to the patron saint of lepers with its 135-foot tower and glorious gilded angels. Tel: (01978) 355808.

Ceiriog Valley Discover the stunningly beautiful landscape beyond the grandeur of Chirk Castle and aqueduct.

The Llangollen Railway, Llangollen There are trains at weekends for most of the year, and daily through the summer. Visit www.llangollen-railway.co.uk

Valle Crucis Abbey (Cadw), nr Llangollen One of the best-preserved abbeys in Wales. Visit www.cadw.cymru.gov.uk

Ruthin Gaol, Ruthin A unique and evocative insight into the lives of prisoners until 1916. Tel: (01824) 708281 or visit www.ruthingaol.co.uk

Clwyd Theatr Cymru, Mold The nearest thing to a national theatre of Wales. Tel: (01352) 755114; www.clwyd-theatr-cymru.co.uk

The Stables Bar and Restaurant at Soughton Hall, Northop, Flintshire Award-winning restaurant with horse-racing theme. Tel: (01352) 840577; www.soughtonhall.co.uk

Where to stay

Ty Derw (5-star), Llanychan, nr Ruthin, Vale of Clwyd Ty Derw, home of John and Michele Davies, their rescue donkey and Shetland pony, is converted from an old village smithy, an Elizabethan farmhouse and an atmospheric barn, and has wonderful exposed beams and sweeping views over the Vale of Clwyd. Visitors who need directions in this haven for walkers can simply ask John to draw one of his wonderful maps, based on 30 years of cycling round the lanes. Tel: (01824) 790611; www.tyderw.com Double room B&B £60.

West Arms Hotel (3-star), Llanarmon Dyffryn Ceiriog, nr Llangollen Part of the Welsh Rarebits collection of fine hotels; tel: (01686) 668030; www.rarebits.co.uk. Deep in the Ceiriog Valley in the foothills of the Berwyn mountains, the West Arms Hotel has been an inn for centuries. The award-winning restaurant and hotel lies at the heart in the idyllic village of Llanarmon Dyffryn Ceiriog, where woodsmoke scents the air over carefully-tended gardens. Tel: (01691) 600665; www.thewestarms.co.uk Double room B&B from £87.

Rossett Hall Hotel (3-star), Chester Road, Rossett, Wrexham The recently-refurbished hotel has well-stocked gardens around the Georgian hall which dates back to 1750. Tel: (01244) 571000; www.rossetthallhotel.co.uk Double room B&B from £85.

Born in the North Wales Borderlands that nestle between Chester and Snowdonia, Carol Davis is the ideal guide to the area.

© 2024

© 2024