The phrases ‘British made’ and ‘Made in England’ are reassuring to see. The words symbolise superb quality, and hundreds of years’ of tradition and excellence. Now exciting new brands are upholding old traditions in surprising ways

It is easy to spot where Britain’s abundant natural resources are: the country’s staple industry for centuries was wool, shorn everywhere from Yorkshire to Devon. The clay soil of the Midlands is perfect for pottery production, Sheffield steel and silver point to abundant mineral mining, and Northampton’s shoemaking means cattle can’t be far. There’s silk in Suffolk, cotton in Scotland, and hardware in Birmingham and Coventry. And in Australia, they still call bed linen ‘Manchester’ because of where it was originally made.

Up until the 1760s, more than 80 per cent of Britain’s population worked on the land. The invention of the cotton-spinning jenny and water frame changed everything, speeding up manual production tenfold, making the UK the world’s foremost manufacturing centre and seeing mass migration to urban factories.

By 1850, just 22 per cent of the workforce was involved in agriculture, and Britain became the first country to shift its economy from agriculture to manufacturing– and still holds the title of the world’s sixth largest manufacturer.

Some textile brands successfully made the leap from cottage industry to factory production. The oldest in the world is Wolsey, founded in 1755, while J Smedley and Johnstons of Elgin arrived in the 1780s and 1790s, followed by Pringle in 1815. All four are respected for their quality yarn and weaving. Similarly, the famous West Country carpet manufacturers Axminster and Wilton switched to machine weaving for the increasingly wealthy industrial middle classes.

Two more early centres of industry were Sheffield, hub of the country’s steel and silver trade from the 1500s and still regarded as the benchmark in fine cutlery, and Staffordshire, whose combination of local clay, lead and coal made it important in pottery production from the 1600s, with Spode, Wedgwood and Minton founded between 1750 and 1793.

Brand heritage

The 1800s saw the foundation of many clothing brands. They tell the story of the constant importing and exporting of style between city and country, military and civilian. Burberry clad the first man to reach the South Pole in its waterproof gabardine, while Aquascutum dressed soldiers in the trenches. Those soldiers returned from war wearing their trenchcoats and turned them into fashion items. Crombie, J Barbour & Sons and Lavenham of Suffolk still produce tweed, waxed and quilted jackets that are as fashionable in Chelsea as in John O’Groats, while Hunter – who shod soldiers in sturdy boots during the war – now supply country dwellers and music-festival fans alike, with colourful wellington boots.

Today, fashion pours around £21bn into the UK economy. “We have a long history of producing quality materials and great design training,” says Kate Hills at Make It British, an organisation that promotes UK brands. “The really great brands combine the two.” They also include some of the most innovative designs on the world’s catwalks, headed up by the maverick grande dame of fashion Vivienne Westwood, highly respected for her tailoring, leading a raft of new conceptual designers. Stella McCartney, Giles Deacon, Matthew Williamson and Christopher Kane keep British fashion at the cutting edge, while premier milliner Philip Treacy creates fabulous headwear for society ladies. Even undergarments are created by Britain’s specialists: The Queen’s foundation fitter Rigby & Peller seamlessly twists tradition and modernity while sexy newcomer Agent Provocateur has a French name but a very British background.

British Tailoring

Superb gentlemen’s tailoring is still considered a supremely British skill, and London’s Savile Row is home to the kingpins of the trade. Henry Poole & Co invented the tuxedo in the 1880s, while Ede & Ravenscroft are said to be the oldest tailors in London, dating from 1689 and still producing ceremonial robes for royalty. Others have celebrity connections: Chester Barrie was a favourite of Cary Grant, Davies & Son of Clark Gable, and Nutters suited Mick Jagger and the Beatles. Alongside them are a whole new breed of names, with Ozwald Boateng, Richard James, Nick Tentis and Paul Smith blending technical know-how with the eye of the 21st-century dandy, and Dashing Tweeds using ultra-traditional materials to create super-contemporary trainers and cycling suits.

For shirts, high quality is in evidence at Hilditch & Key, Emma Willis, Duchamp, Harvie & Hudson, TM Lewin, Thomas Pink and Turnbull & Asser. Accessorise with natty Albert Thurston braces and fine-knitted Corgi socks, or perhaps an umbrella from Swaine Adeney Brigg, also famous for creating Indiana Jones’s felt hat. “Britain has some phenomenal attributes that reflect our brands: politeness, respect for quality, integrity and correctness,” points out Mark Henderson, Deputy Chairman of Gieves & Hawkes (who have measured customers from Lord Nelson to David Beckham). “This is combined with the fact that London is the most diverse population of any city in the world, with a lot of different influences, talent and a constant influx of new ideas.”

Leather trade specialists

Leatherworking is another example of the craftsman’s skill that is still relevant today, reaching its pinnacle in Northampton’s shoemaking trade, with knowledge passed from father to son since the 1200s. Some of the highest quality shoes in the world come from 200-year-old Trickers, who still make footwear by hand for the Prince of Wales. While Grenson, Crockett & Jones, Church’s, Loake, John Lobb, Edward Green, George Cleverley and Alfred Sargeant, while Oliver Sweeney, Mr Hare and Gaziano & Girling cater to the many well-heeled contemporary feet. British women have historically looked to Italy for designer footwear, but Jimmy Choo is a home-grown name that has established a high-profile footfall internationally.

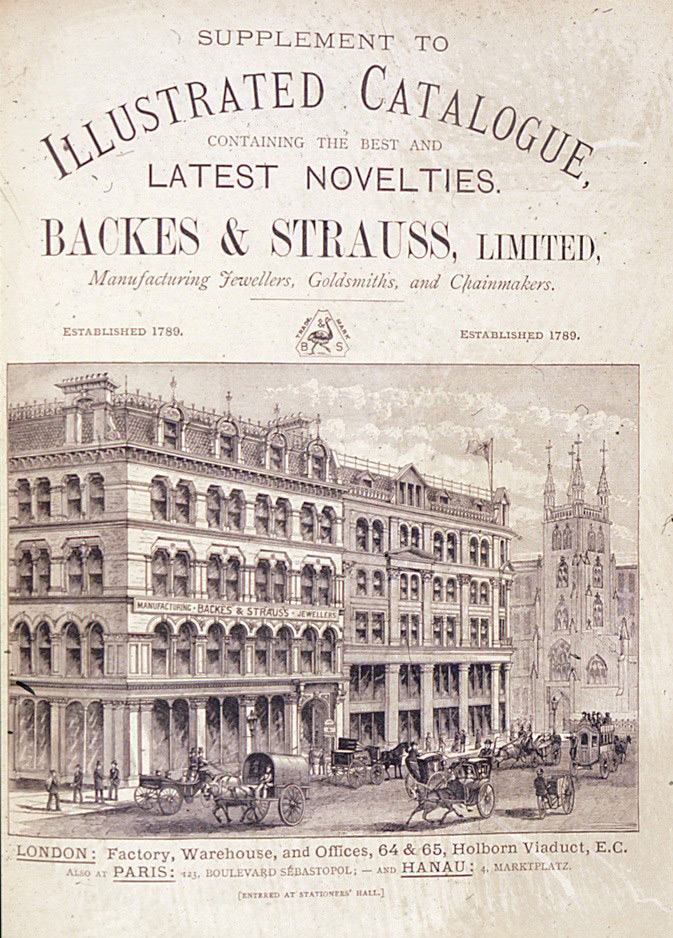

And while the 20th century saw leatherworking dwindle due to cheaper foreign products swamping the market, some old brands still survive: Dent’s has been producing butter-soft gloves since 1777, including those worn by The Queen at her coronation; her ancestor Queen Victoria scribbled her thoughts in a Smythson leather-bound manuscript; while Jackie Onassis commissioned Tanner Krolle, now specialists in sturdy luggage and handbags. Other great luggage makers were Alfred Dunhill, who moved from saddlery to the automobile industry, and Papworth, whose exquisite luggage recalls the great days of rail travel. For chic accessories, there are Ettinger’s sumptuous wallets and purses – with surprising flashes of colour inside – plus relative newcomers Cherchbi, Bill Amberg, Aspinal and Knomo, who blend a solid leatherworking expertise with contemporary designs. Family-run Mulberry is a true British success story, still operating out of Somerset but on an international scale. Also for handbags, the witty retro Lulu Guinness and chic Anya Hindmarch dominate, with recently established Safor offering a range of off-the-peg or bespoke handbags from ethically sourced materials. In the fine jewellery market, jewels arrived through Amsterdam or Rotterdam to be set by Asprey, Garrard, Mappin & Webb, Boodles and Backes & Strauss. Theo Fennell and Tateossian continue to raise the bar with modern designs.

| next page >> |

© 2024

© 2024