Once voted the National Trust’s most haunted property, Blickling Hall in Norfolk is steeped in history. We chart the history of the former home of kings, queens and earls…

Every year on 19 May, Norfolk locals jostle at the gates to Blickling Hall to look out for Anne Boleyn. You would be right in thinking she is long dead. The second wife of King Henry VIII was beheaded for high treason – adultery, incest and plotting

to kill her husband – on that fateful day in 1536.

Not that this stops the curious. Her ghost is rumoured to return to the house at midnight, dressed in white and carrying her severed and bloody head. She is said to arrive by coach, drawn by a headless horseman and four headless horses. She then glides into the Hall and roams the corridors until sunrise.

Anne was born on the 5,000-acre Blickling Estate in about 1501 (the exact date is unknown) to Thomas Boleyn, later the first Earl of Wiltshire, and his wife Elizabeth, and some believe she feels the need to return.

The queen is just one of Blickling’s royal connections. The estate’s stately past begins in the 11th century, when Harold Godwinson, the same King Harold who was shot in the eye at the Battle of Hastings, held the land. “It’s always had that prestigious ownership,” Jan Brookes, the house and collections manager, says: “If you had Blickling, you were somebody.”

In the 15th century, Sir John Fastolf of Caister (the model for Shakespeare’s Falstaff) was just that man, before it fell into the hands of the Boleyn family.

Not that the wandering ghost of Anne would recognise the current building. Her childhood home was taken apart on the orders of Sir Henry Hobart, Lord Chief Justice of the Common Pleas and the first Baronet, who bought the property in 1616, and the property we see today is an evolution of Hobart’s new building, added to by countless titled owners through the years.

Throughout all these years, each owner has made their mark, resulting in a joyous mix of styles within and between rooms. “Blickling has always been about pleasure and leisure,” says Jan. Philippa Hobart, the wife of Sir John Hobart, the 3rdBaronet, for example was a big spender in the 17th century, and bought a lot of fine furnishings. The Victorian era was also a time of travel and all its resulting “clutter”.

Visiting out of hours, I get to see another side of Blickling: staff dusting the carved wooden statue of Anne Boleyn in the Great Hall, cataloguing some of the 12,000 ancient books in the Long Gallery and doing the weeding in the 450 acres of parkland. There’s a surface liveliness and a deeper eeriness about the place: as the National Trust staff cheerfully work away, they conjure up elements of the past.

But which elements? For a start, the most imposing feature of the Great Hall of this red-brick Jacobean mansion turns out not be Jacobean at all. The double staircase was an improvement by John Hobart, the 2ndEarl of Buckinghamshire, more than 100 years later in the 18th-century. “It gives a real sense of arrival,” says Jan. The huge 12-panelled stained-glass window behind it might be from the 15thor 16thcentury, but it wasn’t installed until the 19th century. It was then removed in 1935 because it didn’t suit the owner Philip Kerr’s tastes and packed off to St Mary, Erpingham. In the 1990s, however, Blickling Hall decided it wanted the window back – so it was returned. Philip had preferred plain glass.

There’s a similar story in the Brown Drawing Room. In the original Jacobean design, there were two rooms here: a chapel and an ante-chapel. In the 18thcentury, it became the bedchamber and dressing room for the 2ndLady Buckinghamshire. From the mid-19thcentury, the dividing wall was knocked down to create a morning room for Lady Constance Lothian. Previous owners and guests from other eras will also puzzle over the ornate ceiling, which was painted by John Hungerford Pollen in the 19thcentury. Philip, however, was not a fan and installed a suspended ceiling and cornice in the room to cover it up. After a flood at Blickling in 2002, the National Trust decided to open up the original design to visitors – and here it is again.

Other grand pieces in this room tell stories of yet other times: the chimney piece, decorated with angels, was installed by Falstaff and came from nearby Caister Castle in the 15thcentury. Jan suggests it was originally a window. The William Kent gilded table is much newer, dating from the early 18thcentury.

As for the dining room, it was originally the parlour. The chestnut panelling on the walls might look Jacobean, but was installed in the 18thcentury when the room changed its use. The marble fireplace still has the original Jacobean over-mantle from 1627, but that almost didn’t stay. “When the 2ndEarl took it on in the 18thcentury, his wife hated it,” says Jan. “She threatened to burn it down when he went to London. They had terrible arguments. But he loved it – and it’s still here.”

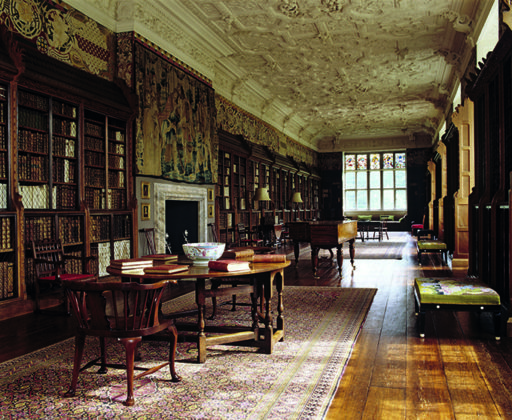

Yet other rooms have had dramatic changes in their purpose. Sir Henry Hobart originally used the 123ft Long Gallery –which now houses one of the most significant libraries in Britain – for indoor exercise in cold weather.

Meanwhile, the State Bedroom, with its Ionic columns, rare Axminster carpet and Italian cassone (an Italian wedding chest) has never been used as a bedroom, let alone one for royalty. “It was a room for best,” says Jan, “and we’re still waiting.” Another room was created simply to display a tapestry of the Battle of Poltava, albeit an incredibly large one (21ft) given to the 2ndEarl of Buckinghamshire in the late 18thcentury by Catherine the Great.

The West Turret bedroom was originally the main bedchamber and closet of the Jacobean house and, incredibly, is still a bedroom. But not everyone has wanted to sleep there. During the Second World War, Blicking Hall served as the officers’ mess of nearby RAF Oulton. One officer was given this room, but he felt deeply uneasy and refused to spend more than a night in it because of the rumours that it was haunted. And not even by Anne Boleyn.

It was once the bedroom of Sir Henry Hobart, the 4thBaronet, who died in a duel on nearby Cawston Heath. Even the décor couldn’t entice the officer to stay. The painting over the fireplace is the left half of a work by Canaletto of Chelsea from the Thames (the right half is in the National Museum of Fine Arts in Havana, Cuba). Canaletto cut the painting himself, as the original commissioner didn’t want it anymore, which made it easier to sell.

The garden has been through dramatic changes, too. A Doric temple and a ha-ha appeared in the early 18thcentury, a fountain (originally at Oxnead Hall) was installed a few decades later, and an orangery was built a few more decades on. The now 1km serpentine lake was just a small formal pool in the early 18thcentury, too. Today, the big improvement is the impressive rejuvenation of the four-acre acre walled garden. After years of lying barren, it now yields fruit and vegetable for the visitor café.

© 2024

© 2024