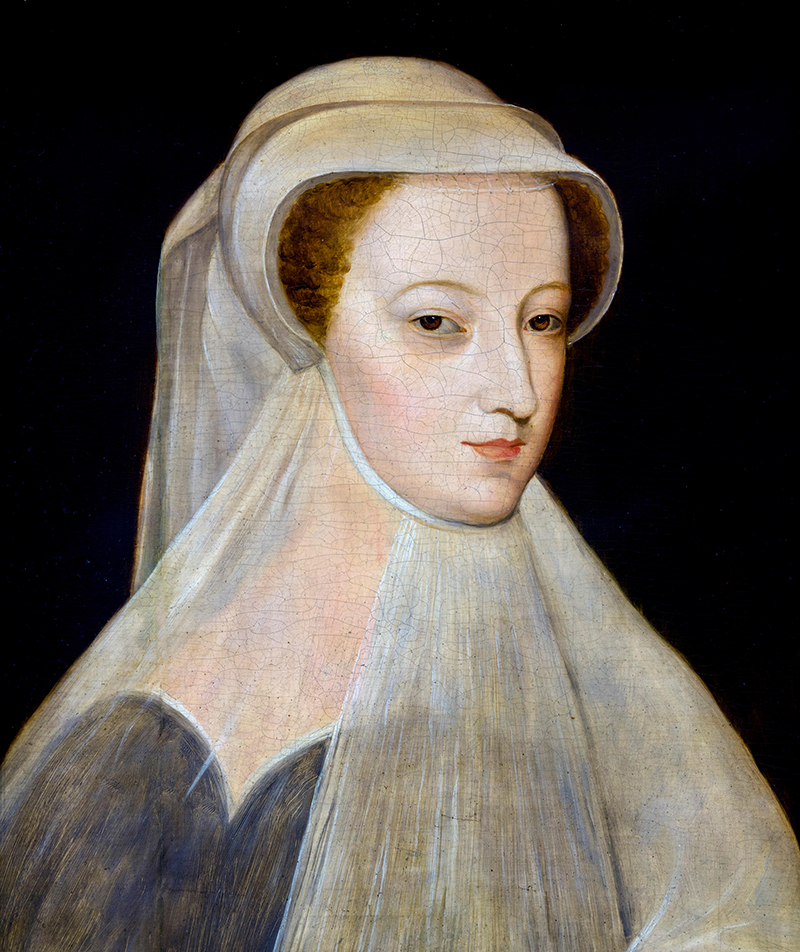

There have been few monarchs in British history quite as tragic or beautiful as Mary Queen of Scots. We sift the fact from the fiction

On 8 February 1587, Mary Stuart came to a sticky end. Dignified, she uttered her last words: ‘Into thy hands, O Lord, I commend my spirit’ (in Latin) and awaited her fate in the stocks at Fotheringhay Castle in Northamptonshire. She had been imprisoned for 19 years. Her second cousin, Elizabeth I, had seen her as a threat to the English throne.

The executioner’s first blow met the back of Mary’s head. The second severed most of her neck, except for a string of tissue which the executioner nished off with his axe. Holding her head up, he proclaimed: ‘God save the Queen.’ Then: thud. Mary’s head fell to the ground. As the executioner clutched her wig, Mary’s terrier shot out from under her skirt, no doubt in shock, like all the onlookers – and now a reader or two.

Fact or fiction? The real story of Mary Stuart – also known as Mary, Queen of Scots – has become intertwined with biased accounts, biographies, novels and lms. The latest on-screen drama is due out in the UK on 18 January starring Saoirse Ronan as Mary and Margot Robbie as Elizabeth.

As enchanting as Mary’s story might be, there is little consensus on her life. Was she doomed as the Catholic monarch of Protestant Scotland, the victim of noblemen who implicated her in various crimes – including the murder of her second husband, and plots to kill her cousin? Or was she a poor ruler of Scotland, failing to unite warring factions, because she was more concerned with landing the English throne?

Her life makes intriguing reading. Mary was born on 8 December 1542 at Linlithgow Palace in Scotland, the only child of James V of Scotland and his French wife, Mary of Guise. She was six days old when her father died and she became queen, her mother acting as regent. She was crowned at Stirling Castle. Aged five, Mary was betrothed to Henry VII’s son, Edward. Her Catholic guardians, however, opposed, matchmaking her with Francis, the four-year-old

heir to the French crown. Off she went to the French court of Henry II, where she spent the next 13 years. In 1558, she did indeed marry Francis, becoming Queen of France when he acceded the throne in 1559. Yet, he soon died of an ear infection.

A widow at 18, Mary returned to Scotland, a Catholic monarch in a Protestant country. She soon married Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley and her rst cousin. Elizabeth I,

by then on the throne, felt threatened by the marriage, because both Mary and Darnley were claimants to the English crown. Their children, should they have them, would inherit an even stronger, combined claim. Mary, however, faced other concerns. Dissatis ed with King Consort, Darnley demanded to be co-sovereign of Scotland. Mary refused. With Darnley in a sulk, Mary grew close to her adviser, James Hepburn, 4th Earl of Bothwell. Disgruntled, Darnley turned to the court’s Protestant nobles for advice. What advice. In 1566, Darnley and his gang burst in on Mary while she was having supper with her secretary, David Rizzio, and ve friends, including Bothwell. Picking on Rizzio, they stabbed him 56 times. They claimed he was trying to get close to Mary for power.

Rizzio’s murder did little to help Mary’s marriage, with Mary and her nobles soon discussing how to remove Darnley. Fearing for his safety, Darnley scarpered to his father’s estate in Glasgow. Mary, however, often visited and a reconciliation seemed near, so when there was an explosion at the estate and his corpse was found outside, her involvement was unclear. Instead, the murder was pinned on Bothwell.

Three months later, Mary married Bothwell, turning Scottish nobility further against her. Bothwell was exiled, and Mary was forced to abdicate. She was imprisoned in Lochleven Castle, Kinross-shire; her young son, James, becoming king. A year later, she fled to England to seek refuge with her cousin, Elizabeth I. Mary had hoped Elizabeth would support her: they were family. But Mary was seen as the legitimate ruler of England by many English Catholics. Elizabeth had her imprisoned. For the next 19 years, Mary was implicated in various Catholic plots to assassinate the queen. Yet without evidence, Elizabeth refused to take more drastic measures, allowing her a few luxuries instead – staff, fine food on silver plates and tapestries.

In 1586, Mary began writing to Anthony Babington, who wanted to depose Elizabeth. When Elizabeth’s spy, Francis Walsingham, discovered the letters, the Queen was not pleased. Her Privy Council had Mary tried for treason and condemned to death. Mary was executed the following year, aged 44, with her son succeeding Elizabeth in 1603. In 1612, James had Mary’s body transferred from Peterborough Cathedral to the vault of Henry VIII’s Chapel in Westminster Abbey.

What of Mary’s guilt or innocence? There might be little proof that Mary would do anything to get the English throne, but she could have chosen better advisers. Someone should have warned her that wearing a wig for her execution could lead to an inglorious end. Instead, we are left with a picture of the former Queen of Scots, head rolling on the ground at a stately home, possible murderess, possible martyr, beautiful and tragic.

Read more:

© 2024

© 2024