Don’t be a Scrooge! Celebrate the spirit and former haunts of Charles Dickens, the Victorian author who shaped our vision of the modern festive season

On the evening of October 5 1843, Charles Dickens took his place on the stage of the Athenaeum in Manchester. The Athenaeum was a society for the “advancement and diffusion of knowledge”. It had been founded in 1837 to provide education and recreation for the working men and women of the city. However, thanks to a recent economic recession, the club was heavily in debt. Dickens was about to give a speech that, it was hoped, would help raise much-needed funds.

What few of that night’s audience would have realised was that Dickens himself was a troubled man. The author was 31 and, for the past seven years, the success of his books such as The Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist and Nicholas Nickleby had seen him rise to become, arguably, the second most famous Victorian, behind only the Queen herself. However, Dickens’ fortunes had taken a downturn in 1843. His latest work, Martin Chuzzlewit, had seen disappointing sales; his wife, Catherine, was pregnant with their fifth child; and he himself, just like the noble institution he was about to address, was heavily in debt.

But, as he rose to his feet that night, Dickens put his personal troubles behind him and, over the course of 12 or so minutes, dazzled his audience with a speech that extolled the virtues of the educational opportunities afforded by the Athenaeum (in a building that today houses part of Manchester Art Gallery).

His speech brought his audience to their feet and, with the applause still ringing in his ears, he headed back through the streets of the city to the house of his sister, Fanny, with whom he was staying. As he walked, an idea began to formulate; an idea for a book that, he hoped, might rescue his ailing fortunes. A book that would come out in time for, and be sold specifically for, Christmas.

What he could not have envisaged on that drizzly night in Manchester was that the book he was pondering was destined to have a massive impact on the way Western civilisation celebrated Christmas and would become the best known and beloved of all his works. For, it was on those dark streets of Manchester that the seed was sown for the second most famous Christmas story ever told: A Christmas Carol.

Dickens “plunged headlong” into what he termed his “little scheme”. By his own admission, it seized him “with a strange mastery” and, over the course of the six or so weeks it took him to complete the novella, he “wept and laughed, and wept again, and excited himself in a most extraordinary manner, in the composition; and thinking whereof, he walked about the black streets of London, 15 and 20 miles, many a night when all the sober folks had gone to bed”.

Amazingly, it is still possible to follow in his footsteps through some of the locations Dickens strolled as the story took shape. The author began the story in the snowy, fog-shrouded alleyways at the very heart of the City of London. Although he was vague about the exact location of Scrooge’s counting house he does tells us that it was in the shadow of the “ancient tower of a church, whose gruff old bell was always peeping slyly down at Scrooge out of a gothic window in the wall”.

This description certainly fits the tower of the medieval church St Michael’s Cornhill and, since Bob Cratchit, having finally been allowed to head home “went down a slide on Cornhill, at the end of a lane of boys, 20 times, in honour of its being Christmas Eve…”, it has led many to deduce that it was one of the atmospheric old alleyways off Cornhill that Dickens had in mind for his miser’s place of work.

In one of these atmospheric backwaters, St Michael’s Alley, there still stands one of London’s least changed “Dickensian” hostelries, the George and Vulture – a place Dickens most certainly knew well and which he had already mentioned by name in Pickwick Papers. Some say this was the “melancholy tavern” in which Scrooge “took his melancholy dinner” as he made his way home on Christmas Eve. The interior of this atmospheric eatery can have changed little, if at all, since Dickens’ day. They continue to serve traditional English fare, while diners are watched over by a white marble bust of Charles Dickens, who gazes down from his window-ledge perch. Indeed, so indelibly linked is this old tavern with the memory of Dickens his descendants still pay it an annual visit to enjoy a family Christmas lunch.

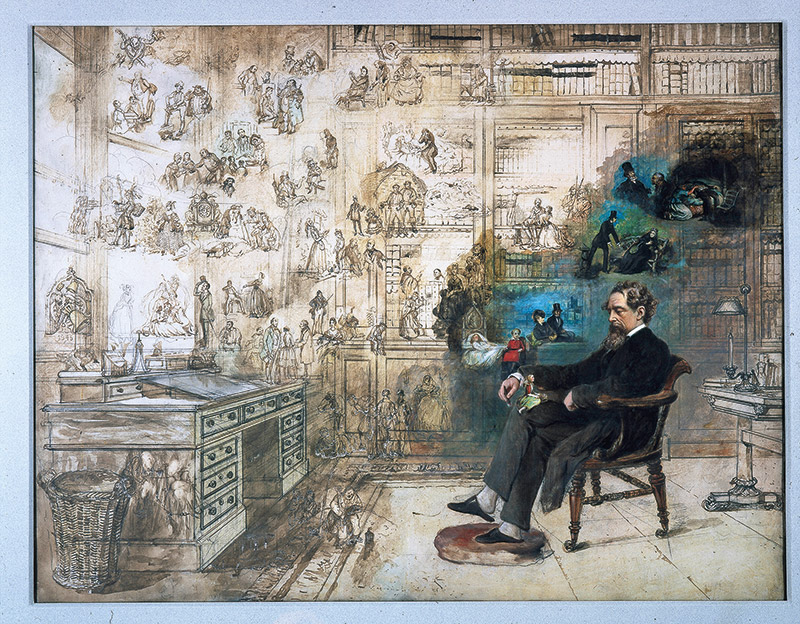

Lebrecht Music and Arts Photo Library/Alamy Stock Photo

As Dickens walked the streets, some of the ghosts from his own past came crowding in and would find their way into the pages of the book. The Cratchits, for example, live in a small terraced house in Camden, north London, reminiscent of the house in Bayham Street in which the Dickens family had lived during Charles’ childhood when they had moved to London from Kent.

When the Ghost of Christmas Past led Scrooge back to his boyhood school where he wept to see his lonely younger self “reading near a feeble fire,” Dickens was, again, remembering his own childhood.

His description of Scrooge’s school as “a mansion of dull red brick, with a little weathercock-surmounted cupola, on the roof, and a bell hanging in it…” is unmistakably of Gad’s Hill Place, just outside Rochester – a house Dickens, as a boy of nine, had often passed on country walks with his father, who had urged him that, if he were to work hard, he “might some day come to live in it”. In fact, Dickens did buy the house in 1856 and it became his principle residence for the last 12 years of his life. Today it is an independent school.

Step by step the story took shape and, by the end of November 1843, Dickens laid to rest the spirits of past, present and future, and transformed his old miser into a man who “knew how to keep Christmas well”. Having penned the final immortal words “God bless us, every one”, Dickens took his pen and, with a flourish, he scrawled “The End”, underlining it three times for emphasis.

A Christmas Carol was published to almost universal acclaim on the 19 December 1843 and, by Christmas Eve, all 6,000 copies of the first print run had been sold, despite its hefty price tag of five shillings. Dickens friend and fellow novelist, William Makepeace Thackeray, declared it “a national benefit, and to every man or woman who reads it a personal kindness.” Another reviewer hailed Dickens as “the poet of the poor”.

People the world over began celebrating Christmas according to the blueprint laid out in its pages. Turkey became the staple meat at the Christmas table, since that was the bird the reformed Scrooge had sent to the Cratchits. There are even records of mill and factory owners, in both Britain and America, being moved to give their workforce Christmas Day off, and treating them to a turkey each, after having read the Carol.

The book captured the public imagination in a way none of Dickens’ other works had, or would, and it remains to this day his most cherished and best-known work. It is as much a part of Christmas as mince pies, turkey and decorated trees. Indeed, so important was Dickens’ contribution to revitalising and reviving the spirit of the season that he is often referred to, quite simply, as the man who invented Christmas. And, to think, it all began in Manchester.

Planning your visit

The London home of the author at 48 Doughty Street now houses an archive of more than 100,000 items and stages regular exhibitions.

This impressive city venue was formerly the Athenaeum, an intellectual society at which Dickens gave the 1843 speech that inspired him to write A Christmas Carol.

Scrooge’s “melancholy dinner” was inspired by this pub off Lombard Street in the City of London, which still welcomes Dickens’ ancestors for Christmas dinner.

With a host of tours available every week, Richard Jones draws on almost 25 years’ experience to bring the author and his books to life on London’s streets.

Words by Richard Jones

© 2024

© 2024