Big Ben, the world’s most famous clock has been under wraps for four years, its iconic bell silenced. This year, restored to its former glory, Big Ben once again shows its face

Words by Rose Shepherd

At 12.01pm on August 21, 2017, something went missing from the soundscape of London. Big Ben, The 13.7-tonne bell that had tolled the knell of passing day for 154 years, through the reigns of six monarchs, fell silent, to be heard only on Remembrance Sunday and New Year’s Eve, as work began on the restoration of the most recognised clock tower on the planet. Since then, hundreds of specialist craftsmen and women – stonemasons, glass artists, painters, gilders and horologists – have brought their skills to the £80 million conservation project.

The clock and tower have stood the test of time remarkably well, despite decades of wear and tear, bomb damage, snow and ice, wind and rain, the ‘pea soupers’ of Victorian times, and modern air pollution.

The effects of such pitiless conditions were keenly felt by conservation teams, working at dizzying heights on narrow gangways, when, in 2018, with the cold snap known as the ‘Beast from the East’ on the rampage, the temperature dropped to -8C, only to soar to 45C in the following year’s heatwave.

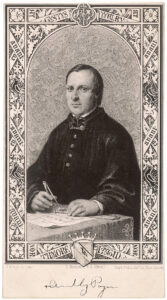

Originally named St Stephen’s Tower, and rechristened the Elizabeth Tower in 2012, to mark Queen Elizabeth II’s Diamond Jubilee, the edifice colloquially known as ‘Big Ben’ was largely the creation of the driven genius Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin, his most iconic contribution to Charles Barry’s Palace of Westminster and its crowning glory.

Completed in 1859, standing 96 metres tall, with 334 steps from ground to belfry, and with the world’s largest and most accurate four-faced striking and chiming clock, this was to be Pugin’s last project. “I never worked so hard in my life for Mr Barry,” he wrote in February 1852 to his friend John Hardman, “for tomorrow I render all the designs for finishing his bell tower & it is beautiful & I am the whole machinery of the clock.”

Aged just 40, Pugin was descending into madness, possibly from mercury poisoning. He would die that September, never to see his plans realised for this beacon of democracy and symbol of the Mother of Parliaments. His letter was only partially coherent. “What he meant to write, in his deluded state,” according to Rosemary Hill, author of God’s Architect: Pugin and the Building of Romantic Britain, “was that he was to design the mechanism… But what he actually wrote was the truth.”

Big Ben is pure Gothic, pure Pugin, and it is his monument. Big Ben, or ‘the Great Bell’, the largest of the tower’s five bells, was cast in bronze at the Whitechapel Bell Foundry in East London, established in 1570, whose name resonates from Philadelphia to St Petersburg. The Whitechapel foundry cast the bells of St Clement Danes of Oranges and Lemons fame. It cast the original Liberty Bell, symbol of American Independence, and the 9/11 Bell, a gift from the City of London to the people of New York.

1858

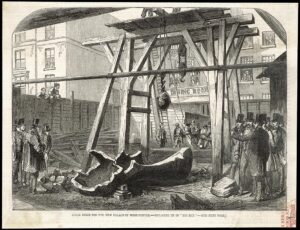

The Whitechapel Great Bell was not, however, the first to be hung in Pugin’s tower. In 1856, with the building incomplete, a bell cast by John Warner & Sons of Stockton on Tees, Co. Durham, made its debut. Predicted to bong in the key of E, it required “six or eight lusty artisans” to tug at the clapper rope. “The vibration penetrates every vein in the body,” The Times reported, “it strikes every nerve, it attacks and tries every fibre in the muscle, it makes your bones rattle and your marrow creep.”

It was as well, then, that, after 11 months, the infernal bell cracked beyond repair. Its lighter replacement arrived from Whitechapel by Thames barge, crossing Westminster Bridge in a carriage drawn by six white horses, as crowds flocked to see it. Initially, it was judged to be little better than its predecessor, its song “so unearthly, sepulchral and miserable, that one would suppose it was tolling the funeral dirge of the whole human race”.

After it, too, cracked, repairs rendered it more subdued, and from November 1863 it rolled out its solemn pronouncements for five miles in all directions, until that August day in 2017 when, for Londoners, it was as if Father Time himself had fallen mute.

Big Ben sends shivers down the spine when it gives voice – and when it does not, whether the clock has been stopped for maintenance, or for reasons of deep historical significance. The bell intoned for the state funerals of Edward VII, George V and George VI. It maintained a speaking silence for two years in the First World War, and for the funerals of Sir Winston Churchill and Baroness Thatcher.

There is a unique, portentous stillness, after the chiming of the Westminster Quarters, an attenuated moment of anticipation, felt most keenly at midnight on December 31 as the bell musters itself to usher in a new year. As Virginia Woolf describes it in Mrs Dalloway, “one feels… a particular hush, or solemnity; an indescribable pause; a suspense… before Big Ben strikes. There! Out it boomed. First a warning, musical; then the hour, irrevocable. The leaden circles dissolved in the air.”

The timekeeping is a wonder of the clockmaker’s art. Designed by Edmund Beckett Denison, a lawyer and amateur horologist, with Astronomer Royal Sir George Airy, the clock was constructed by Edward John Dent, and completed on his death by his stepson, Frederick Dent, with innovative modifications that would set a new standard for tower clocks. The dials, seven metres in diameter, are works of art, framed in cast iron, glazed with 324 pieces of opal glass. The gun-metal hour hands, 2.7 metres long, weigh some 300kg; the copper minute hands, 4.2 metres long, weigh 100kg.

The entire apparatus has had to be dismantled piece by one-thousand piece, for shipping to the Cumbria Clock Company in the Lake District village of Dacre, for overhaul, before being reinstalled. With the progress on schedule, by summer Big Ben should have been reconnected to the original clock mechanism, ringing out regularly once again. The entire project has clearly been an intense journey for all concerned.

“It was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity,” said Keith Scobie-Youngs, Cumbria Clock Company director. “We transplanted the heart of the UK up to Cumbria. We were able to assemble the time side, the heartbeat, and put that on test in our workshop, so for two years we had that heartbeat ticking away in our test room, which was incredibly satisfying.”

“To have had our hand on every single nut and bolt is a huge privilege,” said Ian Wentworth, Parliamentary Clock Mechanic. “It’s going to be quite emotional when it’s all over – there will be a sadness that the project has finished, but happiness that we have got it back and everything’s up and running.”

At the beginning of 2022, as the scaffolding came down, the clock revealed bolder, brighter faces, painstakingly recreating Charles Barry’s colour scheme. Alexandra Miller, Senior Project Manager at Cliveden Conservation, led the team responsible for the restoration of the clock faces. “This was one of the most humbling and career-defining projects we have been fortunate to be part of,” she said. “It cements my lifelong relationship with my beloved hometown of London.” The blackened metalwork of the dial, hands and roman numerals have been returned to the original Prussian blue and gold, with new, white opalescent glass, while the gilt cross and orb at the tip of the tower glisten as in Victorian times, a source of immense pride.

“A clock always absorbs a bit of the person working on it,” Keith Scobie-Youngs has poetically reflected, “and Cumbria will now be linked to this clock for ever.”

Or, as Pugin put it, “It is beautiful, and I am the whole mechanism of the clock.

© 2024

© 2024