With its ancient ruins, hidden coves and seaside villages, Pembrokeshire is surely Wales’s most enticing region

Words by Natasha Foges

Pembrokeshire, the beautiful coastal county at Wales’s southwestern tip, feels wonderfully Welsh, with its green lanes and wild landscapes, sleepy villages and friendly locals who like to stop and chat.

What few visitors realise is that an invisible line splits Pembrokeshire in two. North of the so-called Landsker Line, the Welsh-speaking inhabitants live in Welsh-sounding places: Abereiddy, Llandwa, Porthgain. South of the line, in an area sometimes called ‘Little England beyond Wales’, the locals have been anglophone for centuries, and the place names – Milton, Tenby, Bosherston – have a distinctly English ring.

The origins of this ‘Little England’ can be traced back to 1106, when a series of storms devastated low-lying Flanders (now Belgium). With the blessing of King Henry I, the Flemish sought sanctuary in Britain, settling in the far west of Wales. The colony grew, adopting English as the primary language and forcing the native population northwards. Many of the fifty castles the Flemish built to protect themselves from the Welsh have crumbled into ruins, but the cultural and linguistic quirks linger.

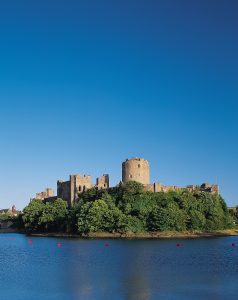

To see the powerbase of the Flemish enclave, head to the county town of Pembroke. Surrounded on three sides by water, magnificent Pembroke Castle is one of Britain’s mightiest and best-preserved fortresses. Charters granted by Henry I and Henry II bestowed privileges upon the town, which brought prosperity, but it is best known for its connection with the Tudor dynasty: Henry VII was born here in 1457.

Follow the castle trail to Tenby, or Dinbych-y-Pysgod to give it its Welsh moniker. The name means ‘Little Fortress of the Fish’ – an apt description of the small tower on Castle Hill, which is all that remains of the massive fortification that once stood here. Built by the Normans in the 12th century, it suffered three attacks by the Welsh before the sturdy town walls – still largely intact – were built.

A core of medieval streets wind down to the town’s little harbour, lined with houses in sugared almond colours and overlooking a golden-sand beach. Summer boat trips visit Caldey Island, occupied by a community of Cistercian monks for a thousand years. You can soak up the serenity of this tranquil place, and perhaps take home a bar of the monks’ homemade chocolate.

Back on the mainland, winding lanes thick with wildflowers lead from Tenby to the hidden cove of Manorbier and its quaint village of stone-built houses festooned with flowers. Almost out of nowhere, a medieval castle rears into view, occupying a commanding perch over the bay. The castle was the birthplace of the 12th-century writer Gerald of Wales, son of a Norman baron and grandson of a Welsh princess, who described it as “the pleasantest spot in Wales”. Biased he may have been, but it’s not so far-fetched a claim. With its turrets, battlements and portcullis, it’s a castle fit for a fairytale.

Further inland is another fine fortress, Carew Castle, which overlooks a 23-acre millpond and, beyond, a patchwork of emerald green fields. The medieval castle was acquired in 1558 by Sir John Perrot, who may have been an illegitimate son of Henry VIII.

Perrot transformed it into a luxurious Elizabethan manor, installing an extraordinary series of vast mullioned windows to flood the medieval building with light – but he died in the Tower of London before his magnificent home was completed.

There are more traces of prosperous living at nearby Lamphey, where the Bishops’ Palace lies in romantic ruin, empty but for the ghosts, some say, of a group of singing nuns. The Bishops of St Davids – powerful, wordly men accustomed to a life of luxury – retreated to this palace to play at being country nobility. You can still see remnants of their Great Hall, sprawling gardens, and the orchards and vegetable gardens that kept them well fed.

St Govan’s Chapel, near Bosherton, presents a humble contrast to the bishops’ excesses. Cut into a cliff that plunges down to the sea, the chapel contains a tiny hermit’s cell, once the lonely lodging of a 6th-century saint. As the legend goes, Govan was being chased by pirates here when a fissure opened in the cliff face, allowing him to slip inside. When the pirates had gone, Govan emerged, founded a chapel on the same spot, and lived here for the rest of his life. The chapel bears rib-shaped impressions, said to mark where Govan squeezed in to hide. Magic is still in the air here: you can count 52 steps down to the chapel, but, locals claim, the number is never the same on the way back up.

Head further north to the diminutive city of St Davids to see the Bishops of St Davids’ main residence, nestled in a picturesque riverside vale. The crumbling Gothic palace, with its arcaded parapet and rose window, provides a dramatic backdrop to the town’s focal point: the 12th-century St Davids Cathedral.

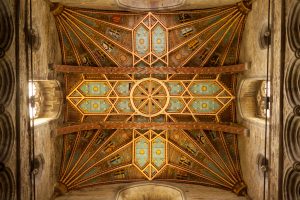

St David, Wales’s patron saint, founded a monastery in the 6th century, from which missionaries spread the word about Christianity to Ireland. The beautiful cathedral, in Romanesque style with an ornate ceiling of carved oak, is thought to be the fourth to be built on the site of the original monastery, and contains St David’s shrine.

It was a centre of pilgrimage for the entire Western world in the Middle Ages: the Pope deemed that two trips here were equal to one trip to Rome. Visit for choral evensong to experience something approaching the wonder that those medieval pilgrims must have felt. Technically, as St Davids has a cathedral, it is classed as a city, but really it’s little more than a village. What it lacks in size it makes up for in charm, with shops, tearooms and galleries painted a rainbow of colours, and the sea shimmering enticingly in the distance. Boat trips depart to the wild islands of Ramsey, Grassholm, Skomer and Skokholm, where you can see an array of wildlife, from porpoises to puffins.

St Davids sits on the edge of beautiful St Brides Bay, which is roughly halfway along the 186-mile Pembrokeshire Coast Path. This scenic trail weaves along the region’s spectacular scalloped coast, past cliffs carpeted in golden gorse, secluded coves and valleys, with views across the sea to offshore islands and swooping gulls.

One of the most dramatic stretches of the path is in the north of the county near Fishguard. A lighthouse crowns a promontory blanketed in heather at Strumble Head, while along the cliffs at Caregwastad Point, a monument marks the site of the last invasion of England in 1797, when four French ships landed on these rocky shores. The troops were to surrender only two days later, having found a farm stocked with brandy for a wedding feast, got drunk and been outwitted by the locals – most famously one Jemima Nicholas who rounded up a pack of twelve Frenchmen, armed only with a pitchfork.

The invaders were also fooled by the sight of what looked like thousands of British redcoats gathering on the clifftops – but in fact was the local women in their traditional attire of scarlet dresses and tall black hats. The triumphant tale is told in the Last Invasion Tapestry in Fishguard’s town hall. Embroidered by local women, it took four years to complete. You can also pay your respects at the grave of Jemima Nicholas at St Mary’s Church, where her headstone commemorates ‘The Welsh Heroine’.

Inland are the purplish Preseli Hills, an expanse of wild moorland dotted with the traces of ancient peoples, including burial cairns and hill forts. The bluestones that stand sentinel here are made of the same stone that was somehow transported from here 5,000 years ago to build Stonehenge – a mind-boggling fact that only enhances the magic of this timeless landscape.

Pembrokeshire could tell its story in stone, but it’s a place that wears its thousands of years of history lightly. Monuments of the past are often a mere sideshow to scenes of sublime natural beauty. A drive down a country lane can yield, unexpectedly, a half-ruined castle or palace, or simply a rocky cove fringed with pink foxgloves. Each makes a lasting impression, quietly imbedding itself in the memory.

None of this is news to the Welsh, who have always seen the magic in Pembrokeshire. The anonymous author of The Mabinogion, an 11th-century collection of folktales, described it as ‘the land of mystery and enchantment’ (Gwlad Hud a Lledrith).

Plan a visit and you’ll surely agree that this little corner of Wales is as enchanting as ever.

This is an extract, read the full feature in the September/October 2023 issue of BRITAIN, available to buy here from Friday 11 August.

© 2024

© 2024