This city of many names has endured centuries of upheaval in its long history. But today Derry~Londonderry, the second largest city in Northern Ireland, is shaking off the shackles of the past and reinventing itself as a thriving capital of culture.

Gliding upriver, a fire-breathing monster seeks revenge on St Colmcille, the founder of Derry, for banishing it to the depths of Loch Ness 1,500 years previously. A dramatic confrontation ensues on the River Foyle as monster and monk battle it out once more, culminating in an explosive fireworks display marking the end of The Return of Colmcille festival. This epic event, masterminded by director Danny Boyle (the man responsible for the opening ceremony of the London 2012 Olympic Games), was a highlight of Derry~Londonderry’s City of Culture festivities.

Christened Derry~Londonderry since its inauguration as the UK City of Culture 2013, the city with many names was originally called Doire (pronounced Dth-ra, in local Gaelic), meaning ‘Oak Grove’, particularly one on an island surrounded by water or peat bog. The name described its environs perfectly. One of the channels crossing a marshy, boggy area at the base of the island of Doire eventually dried out and became known as the Bogside, an area now synonymous with the city.

Doire acquired the name Doire-Colmcille in the 10th century when Colmcille, or St Columba, who set up a monastery here around AD549, became its patron saint. The monastic settlement enjoyed relative peace until the 14th century, when the Normans took over the city, resulting in Richard de Burgh becoming the Earl of Ulster. At this time, Ulster was still not under the English crown. But in 1607 the Gaelic earls finally fled leaving Ulster leaderless and effectively paving the way for ‘The Plantation’ of the province.

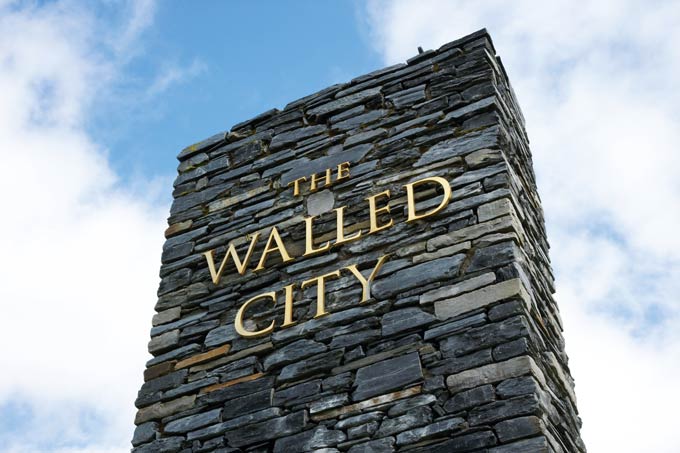

In an effort to claim Ulster, King James I of England/VI of Scotland invited merchants from various London corporations, or guilds, to ‘plant’ loyal followers in the city – mainly Presbyterians. The city of Derry, a shining example of a plantation city, was granted a royal charter by James and given the prefix London – to show its association with the crown. The planters laid a new town plan, which included building walls around the city to defend it from possible reclamation. Londonderry was the last walled city to be built in Europe, and is one of the finest examples of a complete walled city still standing.

Martin McCrossan, who has been running guided tours of the city for 20 years, says, “The favourite part of the tour for most visitors is being able to walk along the well-preserved walls, which are now 400 years old.” He is certain that City of Culture status has stimulated people’s interest in Derryy~Londonderry and the tours: “Last year, we had over 54,000 people on our tours, this year already we have seen a notable increase of around 30 per cent.” Indeed ‘Walls 400!’ – an event to mark the 400th anniversary of the walls – is set to draw even more crowds to the city.

One of the most significant events in the city’s history began in 1688, when troops of the ousted Catholic King James II of England attempted to take control of the garrison. James hoped to launch a campaign from Ireland to regain his crown from William of Orange.

But Derry’s Protestant inhabitants were fearful of a massacre and a group of 13 apprentice boys closed the gates on the attacking army, heralding the start of the Siege of Derry. For 105 days, the people of Londonderry fought against canon fire and mortar bombs, with both sides existing in quite appalling conditions. On 18 April 1689, King James, frustrated that the city wasn’t already taken, arrived at the gates demanding the city submit to the crown. Cries of “No surrender” went up; a slogan that continues to be used by the loyalist population today. Around 7,000 people were lost in the Siege of Derry, and today the same canons used in the crossfire stand sentinel on walls that have never been breached, giving Derry the nickname ‘The Maiden City’.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, Derry became a popular emigration port for those seeking a better life in America, mainly from the introduction of Penal Laws preventing Catholics and Presbyterians from extending their areas of worship, but also due to the Great Famine, which caused a huge reduction in population across Ireland. In World War II, the position of the city on the edge of the Atlantic saw it play a key role in the war effort. The first US naval base in Europe was set up at Beech Hill Estate, only a few miles from the city centre. After the end of the war, Derry became a leader in the textile industry, with many employed in the shirt factories.

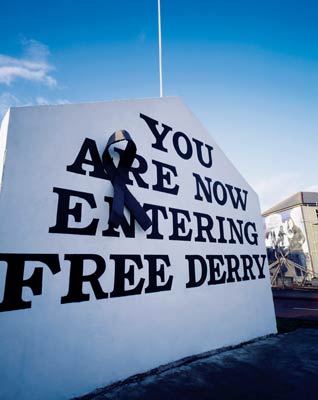

In the 1970s though mass unemployment caused much civil unrest and it was during this decade that ‘The Troubles’ began. Unionists and loyalists, who mostly came from the Protestant community, wanted Northern Ireland to remain within the United Kingdom. Irish nationalists and republicans, from the Catholic community, generally wanted it to leave the UK and join a united Ireland. The Battle of the Bogside riot in 1969 revealed tensions in the city to be at an all-time high.

In January 1972, an anti-internment march descended into chaos until the army fired live rounds into the crowds, killing 14 people. This was Bloody Sunday. Since this tragedy, Derry has been closely linked to The Troubles, but it is an image the people of the city are now successfully moving on from. The majority of Northern Ireland wants lasting peace.

In June 2011, the Peace Bridge was opened, in a move to improve relations between the Protestant and Catholic communities. The old Ebrington Barracks used by the army for many years has been turned into a community space, and this plays host to many UK City of Culture events, including Radio One’s Big Weekend.

Derry’s music and art scene is positively thriving, with the Fleadh Cheoil na hÉireann in August – the biggest festival of Irish culture in the world – drawing crowds of up to 300,000 people and 20,000 musicians to the city. Galleries like the CCA, Void Gallery and London Gallery are hosting exhibitions all year round, with Derry being this year’s city to host the prestigious Turner Prize.

Walking across the Peace Bridge to the newly refurbished Ebrington Square, the excitement in the air is almost palpable. The next generation isn’t focusing on Derry’s troubled past; it is only looking forward, keen to embrace new technologies, new times, a new beginning.

Related articlesPlaces to visit in Belfast |

Click here to subscribe! |

© 2024

© 2024