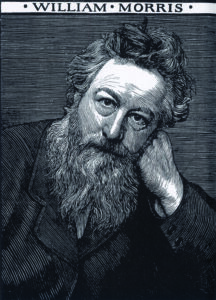

William Morris’s idyllic Cotswold retreat has reopened after a three-year renovation. We step inside to uncover the stories and scandals of Kelmscott Manor

Words by Henrietta Easton

A sunny day in June was the ideal time to visit the newly reopened Kelmscott Manor, dripping in lush greenery, its door framed by perfectly placed roses, with that evocative smell of English summer in the air. Once the country retreat of William Morris, the textile designer, poet, novelist and father of the Arts and Crafts movement, Kelmscott reopened to the public this spring, after three years and a £6m renovation.

Set in the beautifully unspoilt Cotswold village of Kelmscott, Oxfordshire, the manor had been closed to allow for structural repairs to be made to the house, and for the redisplaying of original furniture and artwork to provide a more accurate impression of what the house would have looked like in Morris’s day.

Approaching the house, walking past quaint cottages, farm buildings and green fields, you get a sense of the beauty and seclusion that so inspired Morris, and you’re left in no doubt as to why he referred to the Manor as ‘heaven on earth’.

When Morris first came across this exquisite example of 17th century Cotswold architecture, he felt so inspired by the craftsmanship of the house, the history of the landscape, and the flora and fauna of the gardens that he took on the tenancy.

Morris rented Kelmscott Manor for 25 years until his death in 1896, initially as a joint three-year lease with his friend, the Pre-Raphaelite artist, Dante Gabriel Rossetti. During this time Morris established himself as one of the country’s foremost designers, becoming the owner of his own furnishing and decorative arts firm Morris & Co in 1875, and beginning his renowned experiments with textile dyeing and weaving.

Thanks to Morris’s legacy, Kelmscott is now widely recognised as one of the most significant collections of late Victorian decorative art in the country. Visitors can see an incredible collection of Morris’s possessions and works, including furniture, original textiles, pictures, carpets, ceramics and metalwork.

The manor gardens are a perfect haven, with the expertly designed and beautifully manicured walled garden standing adjacent to wild meadows. The gardens also house a group of historic barns, a dovecote and a stable, once home to ‘Mouse’, the Icelandic pony that Morris brought back from the country for his daughters.

Wandering through the estate gardens, Morris’s inspiration is clear: so many of his beloved designs and motifs grew from plants and trees growing in the verdant space, such as Willow Bough (1887) and the iconic Strawberry Thief (1883). Each of these designs are repeated again in textiles inside the manor, from chairs and wallpaper to plates and curtains.

After Morris died in 1896, his widow Jane and his daughters continued the tenancy. May Morris died in 1938, and bequeathed the house to Oxford University on the condition that the contents were preserved, and the public were granted access. The university passed the house to the Society of Antiquaries, London in 1962.

Under May’s strict orders, the house is preserved as it would have been in Morris’s day, and visitors can walk through the rooms he worked in and experience the inspiration he felt when he lived there. From the idyllic views of cows grazing in the nearby meadows to the gardens in full bloom and the sense of history that pervades the house, it’s hard not to feel similarly inspired.

With so many wonderfully decorated rooms, it’s not easy to pick a favourite. Kelmscott’s Curator, Dr Kathy Haslam, likes Morris’s bedroom best: “The room features new hand-blocked wallpaper in the colourway he would have known, and the reinstatement of some of the items precious to him… It has become a space where objects meaningful to Morris have come together again, and express his energy and enthusiasm as antiquary, scholar and collector.”

After the renovation, the house evokes the life and character of its one-time owner more than ever. “Visitors can now enjoy the manor through the prism of Morris,” says Dr Haslam. “It still feels remote, still retains its rural landscape context and the sense of fragile ancientness Morris was so deeply attuned to.’’

Walking through the house, visitors will also notice the paintings, photographs, and a handful of possessions, of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Morris’s friend and co-tenant. Adorning the walls and complementing Morris’s beautiful motifs, many of these paintings and photographs are of Morris’s daughters, and even more are of his wife, Jane. Though there’s evident harmony between the artwork, the house and Morris’s interiors, digging a little deeper reveals a sadder story.

There was another reason Morris was so eager to rent the secluded manor, away from the hustle and bustle of the city – and prying eyes. Around 1865, six years before Morris discovered Kelmscott, his wife Jane began an affair with Rossetti, for whom she modelled. Their affair became the subject of much public attention, with the satirical magazine Punch even publishing an unfortunate cartoon of an adoring Rossetti feeding Jane strawberries.

Rossetti’s paintings of Jane reveal an obvious obsession with her, and although the relationship was extremely painful for Morris, it was his belief that as an autonomous individual, Jane should have the freedom to explore her emotional life. Morris was still in love with his wife, and with her (and, by default, his) reputation on the line in London, looking for somewhere where she could be with Rossetti in private was critical; and so appears Kelmscott Manor.

It is believed that Morris’s pain and emotional isolation during their affair contributed to his decision to travel to Iceland in 1871, almost immediately after he had signed Kelmscott’s lease. For him, an adventure in Iceland was an escape from his crumbling marriage and broken heart.

Jane ended her affair with Rossetti in 1876, due to a dramatic decline in his mental health: he was experiencing schizophrenic-like episodes and was addicted to chloral and whiskey. After his death, Jane admitted that she had loved him, but had fallen out of love with him when he began destroying himself. They did, however, remain friends until Rossetti’s death in 1882, with Jane continuing to model for him on occasion. After his death, Jane embarked on another affair, this time with poet and political activist Wilfred Scawen Blunt, which continued until 1894.

This is an extract. Read the full article in the September/October issue of BRITAIN out on 12 August.

Read more:

© 2024

© 2024