Bishop Auckland, a small Northeast town with big ambitions, is fast becoming a cultural hub

Bishop Auckland, County Durham, was once the playground of the second most powerful man in England. Powerful men don’t usually like to share and, for centuries, the castle here kept its doors firmly locked. The inhabitants of the small market town took it in their stride – they were more interested in life around the nearby coalmines anyway. When the pits closed in the 1980s Bishop Auckland, like so many other mining towns, began to fade away. It would take a new vision to begin to turn things around.

From early medieval times the Bishops of Durham answered only to the king himself. Granted exceptional power to govern the North of England they became ‘Prince Bishops’, as comfortable in their role as warriors as they were men of God. Even Prince Bishops needed somewhere to relax, however, and a few miles away from the city, on a ridge looking out over the River Wear, they found an ideal position for their fortified pleasure palace.

Over the centuries various incumbents of the position remodelled and tweaked Auckland Castle to their own tastes. They hosted banquets and hunting trips, dignitaries and royalty, including kings John, Edward III, James I, Charles I and Queen Victoria.

The castle was in continuous occupation until the early 21st century, owned by the Church of England. Then a small incident began a chain of events that would lead to a cultural earthquake.

A series of rare paintings by 17th-century Spanish master Francisco de Zurbarán was put up for sale. The canvases, Jacob and His Twelve Sons, Biblical founders of the twelve tribes of Israel, had lived in the castle since 1756 when Bishop Richard Trevor, a supporter of the then-controversial Jewish Naturalisation Act of 1753, had purchased them in a highly political gesture.

Wealthy businessman Jonathan Ruffer had been brought up in the Northeast of England. He and his wife Jane had, for some time, been looking for a way to give something back to the area. “The Auckland Project was founded in 2012, the year that Jane and I came to live in Bishop Auckland,” he says. He bought the paintings – then Auckland Castle itself, to keep them in.

Ruffer’s initial idea was to open the castle to the public for the first time, but things soon gained a momentum of their own. A vision developed, one where museums, gardens, parkland, restaurants, world-class exhibitions and other attractions would celebrate the Northeast, employing and engaging local people and volunteers, regenerating the town through arts and culture.

Ruffer is keen to point out this was not some fancy top-down initiative parachuting in to distribute cultural alms to the poor. “We do not aim to bring good things to people,” he says, “nor to do nice things for people. ‘With’ is the key word; we work in partnership with individuals, governments (local and national), other charities, the churches, and all other religions.”

First to open was the Auckland Tower visitor centre in the marketplace, which tells the story of the Prince Bishops and gives a literal overview of the town from a 15m-high platform. It’s a great way of getting your bearings and working out what to visit next.

Below, in the marketplace itself, a former bank has reopened as the Mining Art Gallery. Moving and deeply personal, it contains work by artists such as Tom McGuinness and Norman Cornish. The themes enjoy a direct link with the town and its people through rolling exhibitions, depicting rugged local communities.

Inspired by the acquisition of the Zurbarán paintings, Ruffer also instigated the Spanish Gallery. This will cover Spanish art from medieval old masters to contemporary works, focusing on the 16th- and 17th-century Spanish Golden Age.

To get to Auckland Castle, visitors pass another building under construction, based on medieval tithe barns. The Faith Museum will trace the history of belief in the British Isles from the earliest prehistoric ritual, through the Northeast’s contribution to Christianity via Saint Cuthbert and the Venerable Bede, to modern expressions of faith. It will include the oldest Christian object ever found in the UK: a pre-Constantinian signet ring with a symbol of fishes, found about a mile away at Binchester Roman Fort.

Also en route to the castle is the gigantic, 14,000-square-acre walled garden. In its 18th-century heyday the garden grew one of Britain’s first pineapples.

A small gate leads to a superb 13th-century deer park. It’s not hard to see why the Prince Bishops built here. Bishop Auckland is as beautiful as it is compact, with a water supply in the river below and steep hillsides making it easily defendable. Don’t miss the crenellated Georgian deer house, from which the Bishops would have surveyed their quarry before releasing it for the chase.

Auckland Castle survived the Reformation, after Bishop Cuthbert Tunstall sensibly signed Henry VIII’s Act of Supremacy, keeping both his head and his lands. Alas, the castle fared less well a century later during the English Civil War. It was sold and partly demolished.

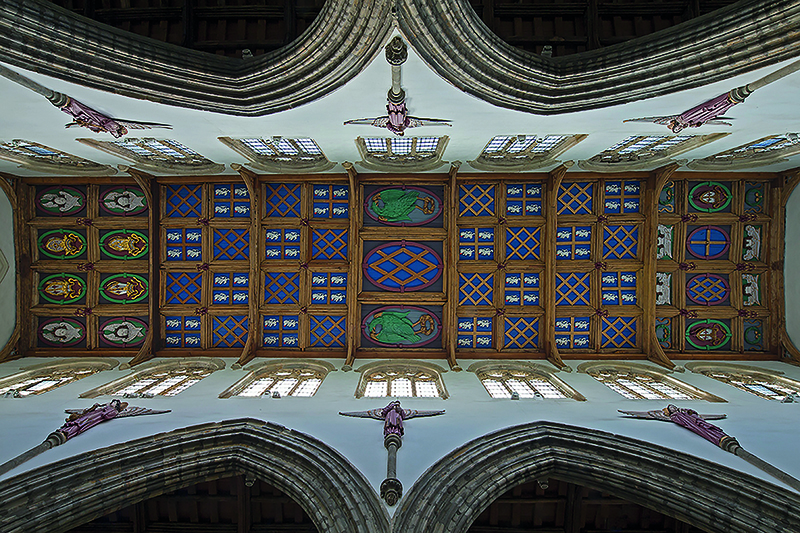

On the Restoration of Charles II the Church got the castle back in ruins. In a slightly unusual about-face to the fate of most country houses, the former medieval Great Hall was turned into a church. It remains as solemn and awe-inspiring as it must have been four centuries ago.

During the 18th century much of the rest of the castle was remodelled in Gothic style. It was designed for frivolity, its lightness reflected in a rainbow of pastel-coloured wall and white-painted tracery.

Some exciting discoveries were made during restoration, such as the original Tudor servery in the kitchens, carved with the phrase Est Deo Gracia (Thanks be to God). This was a time-saving device: any food that passed under it was deemed to have already had grace said for it.

Each room recreates the world of a different Bishop of Durham, including the ‘Abolitionist Bishop’, Shute Barrington, and Reform Act opponent William Van Mildert, whose effigy was burned outside his window by the mob. Hensley Henson, who opposed appeasement with Nazi Germany, is shown through his (very untidy) study, while David Jenkins, labelled ‘Bishop of Blasphemy’ by the press but who was outspoken against the closure of the mines, is represented though his daughter’s 1980s bedroom.

Bishop Trevor’s former apartments will house the Bishop Trevor Gallery, an art gallery hosting a programme of world-class exhibitions of fine art.

As Jonathan Ruffer notes, “Real change in a community takes place over generations and our plans are, accordingly, conceived on this timescale.”

© 2024

© 2024