Tower Bridge is a familiar feature of the London skyline, but the people that lived and worked on this iconic structure had long been forgotten – until a new initiative revealed their stories

Words by Sandra Lawrence

Supported by grand castle-like towers clad in Cornish granite and Portland stone, Tower Bridge is as much a part of London as black taxis and beefeaters. It might seem as though it’s been a part of the capital for centuries, but this much-loved landmark is a relatively recent addition to the London skyline.

By the middle of Queen Victoria’s reign there were plenty of river crossings west of London Bridge. There were none, however, to the east. The Thames, one of the busiest rivers in the world, played host to hundreds of tall-masted ships passing into the City that needed to sail unimpeded. Yet people, horses and carts needed to cross, too.

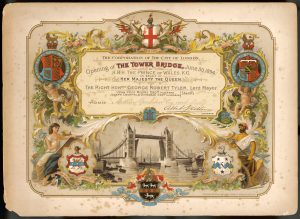

In 1876, the City held a competition to design a bridge that would allow everyone to use the river. Sir Horace Jones and Sir John Wolfe-Barry’s novel design included ‘bascules’ (French for ‘see-saw’) to open the roadway when ships needed to pass through, and a sky-high walkway for pedestrians. Tower Bridge was officially opened on 30 June 1894, by the future King Edward VII, but it was already a tourist attraction. From the start of construction in 1887, visitors flocked to see this marvel of modern engineering in a Neo-Gothic style that complemented its next-door neighbour, the Tower of London (a request by Queen Victoria).

With steampowered hydraulics lifting two great ‘arms’ into the air, by any stretch of the imagination, the project was big. Construction would take eight years, cost £1,184,000 (the equivalent of £122m today), and, under resident engineer Edward Wilson Cruttwell’s eagle eye, employ 432 workers. Until very recently, most of these workers have been entirely forgotten, but an ongoing project researching and reaching out to descendants is now revealing the lives of hundreds of former employees – ordinary people with extraordinary lives.

Among the bravest were the six divers whose back-breaking job was to dig foundations into the heavy clay riverbed. Despite Joseph Bazelgette’s work on London’s sewers, the Thames stank. Visibility, even with underwater lanterns, was almost nil.

A quaker in his 30s, ex-navy and a veteran of the longest pier in the world at Southend, team leader Friend Samuel Penney was one of the rare men in Victorian Britain with lungs strong enough to deal with the pressure ten metres under the water. The work was so dangerous it is said that he trusted no one but his daughter to operate the manual air pump standing between him and the Grim Reaper. An example of the diving suits worn by Penney and his team – James Rouse, James Thacker, Stephen Nott-Fry, Thomas Clucas and Jack ‘Ginger’ William Bateman – complete with massive helmets and lead boots, is on display in a permanent exhibition about the Bridge’s hidden stories. The danger was reflected in the remuneration: Penney was paid 15 shillings a day, but all Tower Bridge workers were well paid; the going rate for a bricklayer was just a shilling a day.

The bascules needed somewhere to swing into when they were opened, so gigantic hollows were dug into the riverbanks. These vast, spooky ‘bascule chambers’ remain empty most of the time, until the bridge opens. They are very occasionally opened for concerts but ships still have the right to demand passage at any hour of the day or night, making scheduling such events difficult. At the turn of the 20th century there were over 9,000 bridge lifts a year. There are now only around 800, but that still averages around twice per day.

Most workers lived locally, and some had less of a commute than others. Bridge Master John Gass’s house – the red brick and stone building on the south side of the bridge – still stands today. Born in Carlisle in 1852, Gass gained his engineering stripes in the Industrial North, at Gateshead. He landed a job in 1886 as a foreman on the Tower Bridge project and was promoted to Bridge Master ten years later. Until his retirement, aged 78, Gass oversaw machinery maintenance, paid wages, certified accounts, ordered materials, and produced any necessary technical drawings.

He, too, was well-paid: a smart uniform, £380 per year, and that lovely red-brick house. Two of his children followed in his footsteps. John’s younger brother James Gass was one of the first six Bridge Drivers. Wearing a livery of waistcoat, trousers, coat and cap, drivers opened and closed the bridge in eighthour shifts across a seven-day week with one day off every three weeks, though in 1913 a six-day week was introduced.

They earned 42 shillings a week. James was eventually promoted to First Assistant Engineer. He didn’t get a house like his brother, though he did live on Tower Bridge Road. The bridge’s staff was large enough to be almost like a ‘household’. Hannah Griggs was born to a single mother in Bermondsey and lived in the workhouse until she was 13 or 14, when she became a servant. Probably the first woman employed at the Bridge, Griggs was a cook, almost certainly for John Gass. The regular workforce had to make their own arrangements, and many reminiscences include the pungent aroma of breakfast cooked on an iron stove, mingling with engine oil and coke. Hannah had to leave when she married a railway firefighter and had her daughter Elsie in 1915.

Tower Bridge was loved from the start, and for many reasons. Even the Luftwaffe realised it was too important to bomb during the Second World War, using it as a marker to locate their real target, the docks. The British people didn’t know the enemy wouldn’t target the bridge, however, and head watchman Ernest Rouse, the bridge’s air raid warden, was as brave as any of the six original divers. His story is one of several displays in the exhibition celebrating labourers, blacksmiths, engineers and clerks alongside hero-Londoners such as bus driver Albert Gunter. When the ‘bridge-opening’ alarm system failed in December 1952, Gunter saw the widening gap, accelerated instead of braking and ‘leapt’ his No 78 double-decker across the already six-foot-wide hole.

The bridge’s high pedestrian walkways were closed in 1910. They had become an informal red light district and a hangout for pickpockets, and most people, especially those with heavy loads, preferred to just wait for the bridge to be accessible at street level rather than tramp up dozens of stairs. The walkways didn’t open again until 1982, when visitors could once again climb the shallow steps to the top and experience fantastic views across the river. Glass floors were installed in 2014, offering a dizzying bird’s-eye view of pedestrians and red London buses crossing the Thames below.

The roadway is still lifted by hydraulics, but since 1976, they’ve been powered by oil and electricity. That doesn’t mean the steam has gone. The Victorian engine rooms remain pristine – and working – maintained by a team of on-site experts. Smooth as silk, the pistons whirr and purr, beautifully painted, oiled and serviced; their dials, cogs and oil-gauges looking like something from an HG Wells novel.

This is an extract, read the full feature in the January/February 2024 issue of BRITAIN, available to buy here from Friday 8 December.

Read more:

© 2024

© 2024