There’s no doubting the effect a place can have on a composer’s imagination and when that place is Britain, that effect can be very powerful indeed. We discover the places that inspired Britain’s musical masterminds

Britain’s landscape can change dramatically in the space of just a few hours, morphing from moorland to craggy coast, from rolling hills to cloud-capped peaks, and from crowded cities to empty plains as far as the eye can see. No wonder Britainhas inspired some of the world’s greatest composers.

But what exactly is it about Britain’s rapidly changing countryside that inspires them? Do composers simply wander the hills and fields in search of interesting features to set to music? The answer is yes, sometimes.

Arnold Bax’s imagination was captured by the ancient, mystical ruins of Tintagel Castle on Cornwall’s sea-battered north coast. The resulting piece called, simply, Tintagel, is a perfect depiction of the place in music. But for many composers it’s the spirit of an area, rather than any specific feature, that fires their musical imagination. The vast skies and the grey, desolate North Sea of Benjamin Britten’s Suffolk; the gritty, hunkered-down remoteness of Maxwell-Davies’s Orkney Islands; the breezy uplands of Elgar’s Malvern Hills, high above a patchwork England – places such as these, rich with emotional triggers, are often what fuel composers’ imaginations.

Somehow the look, smell, feel and sound of a place are translated into music so that anyone with experience of the same area can recognise it in the composer’s music and, best of all, paint their own mental images.

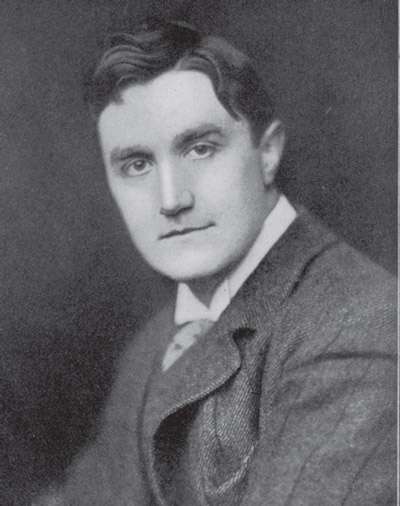

Ralph Vaughan Williams’

The Lark Ascending

Dorking, Surrey

Cricket on the village green, picture-perfect cottages, thickly wooded hills – Surrey is probably most people’s idea of postcard England. Stir in the strains of Ralph Vaughan Williams’ The Lark Ascending and you’ve poured the perfect English cocktail. So what makes the English composer, and this piece in particular, such a powerful ingredient in England’s cultural mix?

Vaughan Williams’ father was a Church of England vicar, his mother the great-granddaughter of the potter Josiah Wedgwood. His great-uncle was the scientist Charles Darwin. For much of his early life, Vaughan Williams lived in the Wedgwood home, Leith Hill House, near Dorking, a busy but pretty market town.

Vaughan Williams’ life was a unique blend of privilege and humility, an accident of birth granting the future composer social status – his experiences and family connections giving him an understanding of the lives of ordinary people and nature’s influence. English folksong was popular among ordinary people and Vaughan Williams would cycle the winding Surrey lanes gathering songs. One fruitful hunting ground was the Plough Inn in the village of Rusper, still a popular watering hole.

Meanwhile, in his depiction of a lark soaring on wings of song, Vaughan Williams was responding to his countrymen’s love of nature with which, through Dorking’s steep-sided lanes encircling Leith Hill, dense woodland and fertile river plains, he was so familiar.

Vaughan Williams sketched The Lark Ascending during the First World War. The world would never be the same again; nor, after his experiences as a stretcher bearer, would Vaughan Williams. But The Lark Ascending plays on, reminding us of a Surrey idyll both real and imagined.

Edward Elgar’s

Enigma Variations

Malvern, Worcestershire

Travel south of Birmingham and the magnificent Malvern Hills, eight miles long north to south, loom alone and proud, rising – not soaring – from a flat landscape to 425 metres (1,400 feet). Hardly the stuff of legend but that’s exactly what they have become thanks to the music of local boy Edward Elgar.

He was born just outside Worcester in the shadow of the Malverns, the son of a piano tuner. Elgar was an ordinary man with extraordinary gifts, a musician who made and kept friends easily and who loved the area in which he lived – he was fond of cycling the Worcestershire lanes, and of playing golf and football.

In later life Elgar moved to nearby Malvern where he rented many homes in and around the town. You can see them all on the Elgar Trail, a well-signposted drive that you can follow today. But Malvern’s distance from Birmingham to the north and London even farther to the south east forced the locals to look to themselves for entertainment. It was just the environment in which a talented composer and teacher fond of music and good company could flourish.

Elgar made many friends and paid tribute to 14 of them in his defining work, the Enigma Variations. One variation, Troyte, is named after his good friend Arthur Troyte Griffith. One day, he and Elgar were out walking on the Malvern Hills when a thunderstorm struck, forcing them to run for cover. The music cleverly recalls the excitement of their breathless dash. If ever a place inspired a piece of music, then the modest Malverns have inspired one of this country’s greatest.

Arnold Bax’s

Tintagel

Tintagel Castle, Cornwall

With its craggy cliffs, golden beaches, crashing surf and bracing winds, Cornwall’s north coast could have been created by Hollywood. Glimpse Tintagel Castle standing guard over the sea some 15 miles north of the quaint fishing port of Padstow, and you would swear it were true.

In fact, Tintagel is a medieval castle that may once have had some strategic usefulness but which, thanks to its part in an 11th-century mythical account of British history as the place where King Arthur was conceived, became shrouded in mystery and fantasy.

Its romantic ruins, battered by the north coast wind and rain, sit on a small peninsula reached by a steep, narrow flight of steps. No wonder that, given such a location and history, it inspired one of Britain’s finest pieces of music.

If anyone was going to be moved by such a place, it would be the English composer Arnold Bax. Both a musician and a poet, blending romanticism and impressionism and influenced by Irish literature and landscape (he had a close affinity with Ireland and lived there on and off for over 30 years), Bax was hugely receptive to Tintagel’s mystique. But it would take a woman to turn his fevered interest into music.

That woman was his mistress, the pianist Harriet Cohen, with whom Bax holidayed at Tintagel for six weeks in 1917. Inspired by her, Bax weaved references to Wagner’s opera Tristan und Isolde, which also features Tintagel, into his heavily charged work. You can sense the drama of their relationship amid the castle’s eerie ruins.

Malcolm Arnold’s

Padstow Lifeboat

Padstow, Cornwall

Thanks to TV chef Rick Stein, who has not one but four fish restaurants in the town, the Cornish fishing port of Padstow has in recent years taken on a whole new character.

It’s still a working port, however, and while Padstow is a pretty picture postcard of a Cornish harbour town, it’s one that, despite the tourist trinket shops and upmarket fish restaurants, retains its traditions and isn’t afraid of hard graft.

Trawler fishing is not for the faint-hearted. When last season’s tourists are safely returned and the town is quiet once more, Padstow’s hardy fishermen are gunning their trawler engines and turning their helms for the waters of the Celtic Sea and beyond.

Many have lost their lives in pursuit of the food of the sea but one plucky band of men is on permanent standby to help them. The crew of the Padstow Lifeboat know fear, but still they brave the sea to help those in peril. They were immortalised by the composer Malcolm Arnold who lived in neighbouring St Merryn and who in 1968, on the dedication of their new lifeboat station, presented them with a fine new march – The Padstow Lifeboat, a March for Orchestra.

It’s typical Arnold – bold, tuneful and shot through with wicked humour, in this case a repeated off-key blast from the brass, representing the blaring foghorn of Padstow lighthouse. How it must make the cutlery shake in Rick’s restaurants!

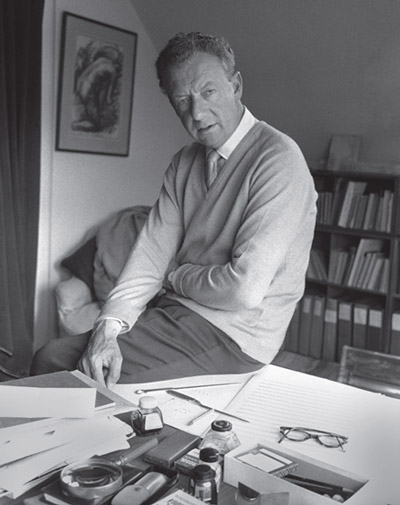

Benjamin Britten

Peter Grimes

Aldeburgh, Suffolk

What is it about the North Sea, the watery grey plain which separates Britain from northern Europe, that fills people with foreboding? Is it the biting easterly winds that blow over it from Siberia to freeze our east coast? Is it the intimidating coastline itself, one lacking the clifftops and sandy charms of our west coast playgrounds?

Whatever the reason, it has inspired one of classical music’s most forbidding and desolate operas – Peter Grimes. Composed by the famous Suffolk-born composer Benjamin Britten, premiering in 1945, it tells the story of a trawlerman, Peter Grimes, accused by the local townsfolk of murdering his apprentice. The judge finds him innocent. However, a friend advises him against hiring another. But a friend persuades him to do just that and when the angry mob finds out, Peter Grimes and his young apprentice head for his boat. Alas, the young lad falls to his death from the clifftop and when eventually his jersey is found washed up on the beach Grimes flees back to the sea, which claims his life.

It’s not a story to put a holiday smile on your face but to Benjamin Britten it was the perfect plot for an opera. He lived in the Suffolk town of Aldeburgh (indeed, he established the now world-famous Aldeburgh Festival at nearby Snape Maltings) so he was well acquainted with the town’s fishing industry.

But that’s to ignore the subtext to the opera, which in Britten’s words “is a subject very close to my heart. The struggle of the individual against the masses. The more vicious the society, the more vicious the individual.” Only the North Sea could provoke such a feeling.

Peter Maxwell Davies’

Farewell to Stromness

Hoy, Orkney Islands

The Orkney Islands lie ten miles off the northernmost tip of Scotland. Their sheltered sandy bays, piercing blue waters, dramatic cliffs and heather-topped moors are home to vast flocks of migrant birds, while pretty white crofts, stoic little towns and bustling harbours are home to a thriving Orcadian community. Given all of this, you can understand why that former enfant terrible of British contemporary music, the composer Peter Maxwell Davies, would choose to settle here. If you’re a composer seeking escape and inspiration, you’ll find it in abundance in Orkney.

But even this visionary musician could not have predicted where one source of inspiration might come from. In the early 1980s there were plans to locate a uranium mine near the village of Stromness. Max, as he is known, composed the Yellow Cake Revue (yellowcake is uranium concentrate), a collection of short pieces, to fight the plan.

One piece in particular stands out – Farewell to Stromness, a simple but beautiful little tune over a walking bass that tells of the Stromness village folk having to leave their homes. Only when you’ve experienced Orkney can you imagine the wrench this would be.

© 2024

© 2024