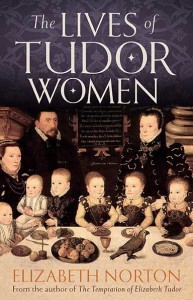

Historian Elizabeth Norton’s new book, The Lives of Tudor Women, explores the seven ages of woman in the turbulent Tudor era. Here, she takes some time to answer our questions on this fascinating subject.

The Tudor age never fails to capture the imagination. The era was dominated by some powerful and iconic women in way that had never seen previously. But what was it like being a woman during this period?

In her new book, Elizabeth Norton explores the seven ages of the Tudor woman, from childhood to old age, through the diverging examples of the women from all walks of life, from the high born to a peasant girl, seamlessly weaving together the expereinces of the powerful with those of ordinary women through their universal experiences.

BRITAIN magazine fired off some questions to the historian to give you a taste of the treats in store in The Lives of Tudor Women and shed light on some little-known facts about the time.

The book focuses on the lives of women from all walks of life. Did the day-to-day life of a Tudor women from different backgrounds share much in common?

They did. Sexual inequality was a major issue for women of all walks of life. In fact, it started in the womb, with girls believed to obtain their souls (and thus be accounted as alive) at 90 days gestation – 44 days after a boy was supposed to become a living person. This continued throughout their lifetimes.

Although the education of women became fashionable early in the 16th century (thanks to the example of the three highly educated daughters of Thomas More), it was not expected that girls be taught the same as boys. One Elizabethan educationalist, who was in favour of female learning, for example wrote that he would speak first of boys’ education, since ‘naturally the male is more worthy’. Some also considered it dangerous for girls to learn Latin or Greek, since it might ‘inflame their stomachs’ towards vice. Nonetheless, by the 1520s, most girls at all levels of society could expect some schooling.

All women were legally subject to their husbands and were therefore unable to own property, enter into agreements or even make their own wills without their husbands’ consent. Their daily lives would also have been similar, with women (from the highest to the lowest) required to run their households, supervise servants and raise their children. A duchess might not actually cook the family’s food, but she would be expected to tend to the injuries of her tenants and servants and provide medicinal advice.

The Tudor period was one of great change. Did these changes directly affect women’s lives during the era?

The Tudor period was one of great change. Did these changes directly affect women’s lives during the era?

Absolutely. The Reformation, along with the often rapid changes to religion that this entailed, effectively required everyone to make a choice as to their religious beliefs and practice.

King Henry VIII considered it dangerous for women to read the scriptures and, thus, come to their own conclusions about religion. In 1543 he passed the Act for the Advancement of True Religion, which restricted the English Bible only to upper class women, who were even then only able to read it in the privacy of their homes. Nonetheless, many women were extremely vocal about their faith, such as Anne Askew, a Protestant who was burned for heresy during Henry VIII’s reign, or the Anabaptist Joan Bocher, who was burned under King Edward VI.

More ordinary women, too, were forced to take decisions. In Mary I’s reign, Protestants were required to abjure their faith and return to the Catholic church. Many upper class Protestants (male and female) chose to leave England, while other Englishmen and women chose to remain, under considerable danger. Elizabeth Cooper, the wife of a Norwich pewterer, initially recanted her Protestant faith when Mary came to the throne but, in 1557, she entered her local parish church and– in front of the congregation– ‘she revoked her recantation before made in that place, and was heartily sorry that ever she did it’. She was soon burned, but not before she inspired another local woman– Cicely Ormes– to take a similar position.

Under Queen Elizabeth I, it was always illegal to attend Catholic worship, although many did secretly. Others became ‘Church Papists’ – obeying the law in attending Protestant church services but still seeking to maintain their faiths. Others became recusants, refusing to attend Protestant services even in the face of imprisonment and crippling fines. In the rapid religious changes of the Tudor period, it was not enough simply to live as before, with women – as well as men – forced to actively choose how they intended to respond.

Henry VIII’s marital tribulations highlight that romance could be a minefield for high-born Tudor women. How different was love and marriage for other women?

Tudor women were expected to marry. At all levels of society it was hoped that there should be love or, at least, some liking between a couple, with a match entered into by compulsion seen by some contemporaries as a match entered into ‘in a forgetfulness and obliviousness of God’s commandments’. However, in reality, most upper class marriages were approached as a business arrangement, with the bride and groom’s fathers haggling over dowries and jointures. Lower down the social scale, women tended to have more choice although young women were urged to avoid the ‘crocodile tears’ of young men who would attempt to persuade them into their beds without the promise of marriage.

Surprisingly, all that was required to contract a valid marriage was a promise and consummation – a church service was not necessary. However, it was sensible to obtain witnesses to the promise. Jane Singleton, from Halsall in Lancashire, was fortunate in 1558 when she persuaded a local man to act as witness when she was promised to a young gentleman named Gilbert Halsall. The couple – without a priest in attendance – stood together at the altar of their parish church, with Gilbert taking Jane by the hand and telling her that, ‘I Gilbert take thee Jane to be my wedded wife and thereto I plight my troth,’ before Jane said the same. However, the next morning, after the couple had gone to bed, Gilbert attempted to deny that the marriage had taken place. Only the witness’s testimony ensured that the marriage was declared by the church courts to be valid. Even higher status women could run into trouble in this way. Catherine Grey, a kinswoman of Elizabeth I, found her secret marriage declared invalid by the queen when one witness died and the other disappeared.

Elizabeth I was famous for her independence. Could women from other walks of life expect to live independently?

Although married women were subject to their husbands in law, other women could be surprisingly independent. The vast majority of teenage girls entered into some kind of service – usually domestic or agricultural. While their first contract of service was usually arranged by their parents or other relatives, serving maids tended to move regularly with most contracts of only one year’s duration. Even the very poorest of girls therefore had some ability to choose their own employment and move around.

Widows, who often inherited the family business and property, could also be very independent. Katherine Fenkyll, who was the widow of a London draper, took over her husband’s business following his death. She ran it successfully, including managing her own small fleet of ships with which to import and export her goods. Although, as a woman, she could not be a member of the successful Drapers’ Company, she engaged her own apprentices and was regularly invited to sit at the top table at company feasts in the 1520s. It may have been with some satisfaction that she noted that the tables were festooned with silver plate borrowed from her house early on the day of the feasts.

In some cases even wives, who were not legally independent of their husbands, enjoyed some level of independence. Under the custom of the City of London, any married woman who ‘follows any craft within the said City by herself apart, with which the husband in no way intermeddles’ would then ‘be bound as a single woman as to all that concerns her said craft’. These femme soles, who traded under their own names, were legally able to enter into contracts, own property and sue or be sued in court, giving them considerable autonomy in spite of the fact they were married.

Women’s familial bonds seem much as they are for us now. What was a mother’s life like?

Family was often central to the lives of Tudor women. Female relatives were expected to attend the births of children, while women were also primarily responsible for the upbringing of their children. Upper class mothers would supervise their children’s early education, as well as often undertaking to raise the daughters of less well-connected family members in the hope that they could secure husbands for them.

In the Tudor period, there was also considerable debate over the role of mothers. Surprisingly then, as now, a debate raged about the benefits of breastfeeding, although in the 16th century this largely concerned whose breast was best. The vast majority of upper class women employed a wetnurse, although this was frowned upon by many contemporaries. Even the great Erasmus waded in, declaring that wetnursing was ‘a kind of exposure’, while for Thomas More, it was a mothers’ duty, with only ‘death, or sickness’ reasons for a mother failing to nurse her own children. Elizabeth Clinton, Countess of Lincoln, who had herself been a Tudor mother, would later write a tract addressed to her daughter-in-law, on the duty to breastfeed. She candidly admitted that ‘I should have done it’, although was dissuaded thanks to claims ‘that it is troublesome; that it is noisome to one’s clothes: that it makes one look old’. Lower down the social scale this was less than issue. With no formula milk, mothers who could not breastfeed usually boarded their children out with foster parents until they were weaned.

The Lives of Tudor Women by Elizabeth Norton is available now, priced £25.

Related articles

|

Click here to subscribe! |

© 2024

© 2024